Home | Call for Papers | Submissions | Journal Info | Links |

Journal of the Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

ISSN: 1854-

Jaroslaw Krajka

University of Social Sciences and Humanities in Warsaw

Audiovisual Translation in LSP – A Case for Using Captioning in Teaching Languages for Specific Purposes

ABSTRACT

Audiovisual translation, or producing subtitles for video materials, had long been out of reach of language teachers due to sophisticated and expensive software. However, with the advent of social networking and video sharing sites, it has become possible to create subtitles for videos in a much easier fashion without any expense. Subtitled materials open up interesting instructional opportunities in the classroom, giving teachers three channels of information delivery for flexible use. The present paper deals with the phenomenon of subtitling videos for the ESP classroom. The author starts with a literature review, then presents implementation models and classroom procedures. Finally, technical solutions are outlined.

Keywords: Captions, subtitles, video, audiovisual translation.

1. Introduction

The use of video has been long established in teaching Languages for Specific Purposes, with numerous benefits often put forward by methodologists and tested in field research. Nowadays, together with widespread access to the internet, an abundance of video materials for teaching virtually every specialization has become easily available to instructors at virtually no financial cost. Given proper training in how to search for and download video materials of various types and file extensions, there seems basically no obstacle to authenticating LSP instruction with an audiovisual dimension.

However, a frequent objection to the use of authentic video materials has been that their didactic exploitation is hampered by lack of compatibility with the language level of target learners. Even though advanced students could be exposed to authentic videos from the workplace, learners at lower levels were put at a disadvantage due to discrepancy between the language level of the video and their own interlanguage.

The purpose of the present paper is to reflect on the phenomenon of audiovisual translation and its applicability in LSP methodology. After presenting the state of the research into the use of captioned video materials in foreign language acquisition, the major part of the paper attempts to lay down the foundations for the use of subtitled videos in the LSP classroom, starting with explaining the methodological rationale, discussing implementation models and concluding with technical solutions.

2. Literature review – Justification for the use of captioned videos in the language classroom

The use of subtitles in videos and TV programs has been met by great enthusiasm on

the part of researchers for various reasons. In several studies the effects of subtitles/captions

on receptive skills and vocabulary acquisition were investigated. The research focus

was mainly on whether captioned videos or TV programs are more effective than non-

In one of the most recent studies Karakas and Saricoban (2012) confirm the significant

relationship between watching subtitled and non-

In her experiment with keyword captions, full text captions and no-

Video-

Danan (2004: 67) claims that audiovisual materials enhanced with captions or subtitles may function as a powerful educational tool in many ways. For example,

1. they improve the listening comprehension skills of second/foreign language learners;

2. they maximize the effectiveness of language learning by helping students visualize what they hear;

3. they enhance language comprehension and lead to additional cognitive benefits, such as greater depth of processing.

Karakas and Saricoban (2012) add that captions/subtitles play an important role in

lowering the affective filter, which psychologically affects one’s learning. For

example, since it is easier for a viewer to understand foreign language films with

subtitles and captions, acquiring a foreign language is more stress-

Gajek (2008) points out the fact that captioned videos are suitable for incidental

learning of vocabulary at all levels of language proficiency. Lower-

On the other hand, as Winke, Gass and Sydorenko (2010: 67) claim, it is difficult to generalize the findings of the previous studies on subtitling for at least two reasons: “First, several studies did not group subjects by proficiency levels; second, the types of tests used to measure the effects of language learners’ processing of captions varied widely”. Hence, the differences in comprehension may have resulted from the effects of captions/subtitles or from the level of proficiency, and it is not fully proven whether other students may produce similar results or not.

Danan (2004) voices another objection against the technique, reporting that many

language teachers are against the use of subtitling in audiovisual materials. This

might be because they fear that subtitles distract learners’ attention, especially

that of lower-

At this point some reflection is needed on the place of resultant subtitling-

While there are diverse impressions of the use of subtitles in language education, undoubtedly due to easy accessibility and educational potential LSP, teachers are encouraged to adapt selected video materials by adding carefully considered scripts either in L1 or L2, either full script or only partial subtitling.

3. Approaches to teaching LSP with subtitled videos

Diverse ways of using subtitled videos in the Languages for Specific Purposes classroom are proposed here. The taxonomy presented below takes as its major criteria who actually produces subtitles and for whom. The term ‘Sub’ in the names of the models below indicates a set of procedures designed to make use of subtitling in the process of language learning, in different modes and with differing amounts of teacher control. With this in mind, three original models are put forward as follows:

3.1. Teacher Sub

The teacher is solely responsible for selecting videos, producing subtitles and making

both available to students. This approach might be favoured when teaching lower-

3.2. Class Sub

This model stands in contrast to Teacher Sub as it acknowledges a much bigger role for learners in the process of preparing materials. While not necessarily producing subtitles themselves, in the Class Sub model the teacher carefully activates learners in those areas in which they can contribute to the class. These might be the following:

· searching for videos of interest on Video Sharing Sites (such as YouTube) for the teacher to caption;

· selecting videos for captioning from the teacher-

· working on teacher-

The in-

3.3. Autonomous Sub

Once learners have been trained in how to make subtitles in one of the easy-

· putting lines in the correct order to produce proper subtitles;

· inserting the missing words (e.g., articles or prepositions) in the subtitles;

· synchronising teacher-

The Autonomous Sub model needs to include the stage of sharing learner-

4. Using subtitled video materials for vocabulary instruction in LSP – Practical techniques and guidelines

When considering how to exploit the medium of subtitles, the major decision to be taken is what language(s) to choose. Gajek (2008) shows various language combinations that can be successfully exploited in language learning:

· L2 audio + L2 subtitles – listening and reading skills are activated simultaneously to reinforce verbal and graphical representation of language.

· L1 audio + L2 subtitles – foreign language reading as well as mediation skills are developed.

· L2 audio + L1 subtitles – listening comprehension is enhanced while giving learners support in making out the meaning for themselves.

· L2 audio + L3 subtitles – integrating foreign language experiences leads to greater awareness of multiculturalism and plurilingualism of the modern world.

The decision regarding which of the above models should be applied depends on two

types of criteria: learner-

Subtitled videos can be used in the classroom using tried and tested techniques of

video implementation (Allan, 1985; Harmer, 2001; Krajka, 2006; Krajka, 2007; Lonergan,

1984; Stempleski, Tomalin, 2001): blind viewing, silent viewing, freeze frame, fast

forward, jigsaw viewing/split viewing, jumbled sequence. These techniques rely mainly

on the fact that while viewing tasks join two channels of perception (aural and visual),

one of them can be temporarily switched off to develop learners’ skills. With subtitles,

the third channel of perception (visual-

· displaying full-

· showing only partial subtitles (e.g., only selected problem words);

· displaying gapped subtitles (with key words to be reconstructed);

· highlighting particular words/parts of speech with bold/colour;

· displaying subtitle lines in the wrong order;

· manipulating display times of subtitles (same as audio, shorter/longer than audio, displayed with delay or prior to audio).

Given the range of possible viewing techniques, the teacher can freely use subtitled materials to enhance the process of vocabulary acquisition in any of its stages. To start with, vocabulary presentation will benefit most from using subtitles in L2 and their L1 translations to reinforce the listening experience. Similarly, for vocabulary presentation the teacher can design some general viewing tasks in which subtitles only play a supplementary role, showing the graphic form of the new words without greater focus on them. Furthermore, making the context of the recording clearer to students and generating their viewing interest in the initial stages of the process can be assisted by subtitles which explain who the characters are, and where and when the story is taking place. Clearly, the Teacher Sub model described above would be most appropriate for this phase of vocabulary acquisition as it is hardly realistic to expect learners to produce subtitles for a new piece of visual material.

Vocabulary practice is the phase of vocabulary acquisition during which learners

recycle newly encountered words to transfer their meaning from their sensory memory

to the short-

Finally, vocabulary production with a communicative purpose involves free selection of vocabulary by learners. The model of Autonomous Sub could be applied here, with learners producing their own subtitle lines based on what they hear or encouraging them to add situation descriptions to captions.

5. Preparing captioned video materials – technical solutions and procedures

The technical part of producing captions for videos encompasses a number of different areas which might demand teacher skills for smooth production of subtitled materials. On the one hand, instructors need to be in possession of a selected video file so that it can be loaded to a subtitling program. For streaming videos (playing ‘live’ from the website, stored at YouTube and other Video Sharing Sites), this involves downloading a video file to one’s computer and converting it from a Flash video (.flv) file to one of the most common formats (.avi, .wmv, .mov, etc.). Downloading and converting can be accomplished with a number of video downloaders, such as YouTube Downloader, or, alternatively, online services such as Keepvid.com.

The second issue to be resolved while preparing videos for subtitling is to make

sure that the computer is equipped with a video player which supports subtitles as

well as codecs required to encode and decode audio and video files of different formats.

Thus, AllPlayer for the former and K-

It needs to be stressed that, generally, the product of captioning is a separate text file (usually with a .txt or .srt extension), which needs to be stored in the same directory as the source video file in order to be displayed properly by AllPlayer. In contrast to producing captions embedded in films, producing a separate subtitle file does not interfere with the integrity of the video material to be subtitled, which is an important copyright issue.

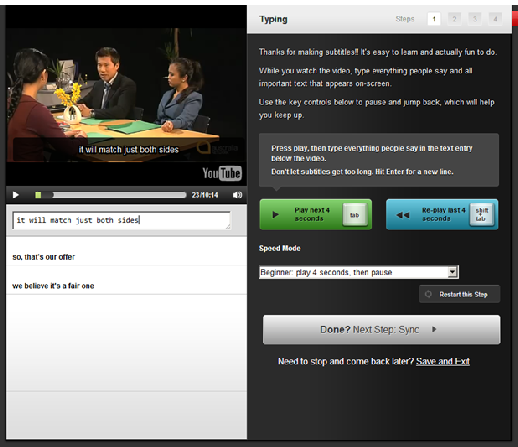

Once the preparatory activities outlined above have been accomplished, the actual process of producing subtitles can start. Depending on the user’s needs and skills, one of the two approaches can be used: an online service or a downloadable program. The former starts with either uploading a video or grabbing a video file from a Video Sharing Site, then the user is guided through the subtitling process in a couple of steps such as uploading a video file, introducing text, synchronizing, adding video information, checking work and producing the resultant subtitle file for download. Two examples of such services are Amara and DotSUB.

Figure 1. Captioning a YouTube video with Amara

Both Amara and DotSUB are free of charge and require only registration. Furthermore,

the former can use existing accounts from some other social media sites such as Facebook,

Twitter or Gmail in order to register. In terms of selecting videos, the former allows

only subtitling online videos, while the latter also allows for uploading a file

from one’s computer. Amara seems to be slightly more user-

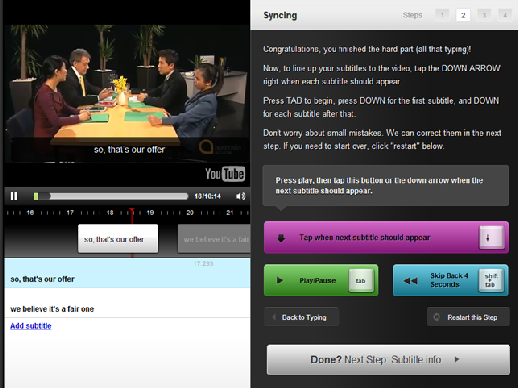

Figure 2. Synchronising subtitles in Amara using keyboard keys

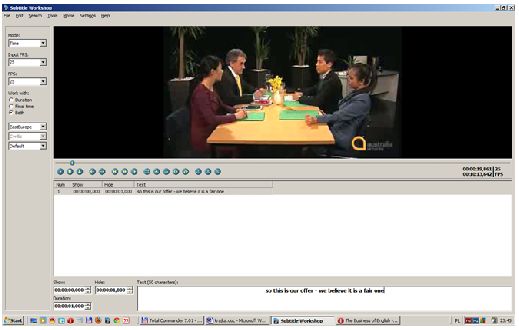

Rather than use online services, which need reasonable bandwidth, a software solution

can be adopted. Similarly, a number of freeware downloadable subtitling programs

are available, differing in the degree of user-

Figure 3. Adding subtitles with Subtitle Workshop

6. Implementing subtitles in a Business English lesson – A practical proposal

To exemplify how to use the subtitled materials in practice, the following proposal

refers to the use of captioning in a Business English course for pre-

1. The whole unit starts with viewing tasks during the initial topics of the curriculum to make learners confident enough with viewing comprehension.

2. Subsequently, the activities based on a script in the printed form follow, so that learners could become skilled at using the two channels: the verbal and the auditory.

3. Next, the printed support is replaced with full subtitles on the screen in further viewing tasks so as to make learners accustomed to reading L2 text.

4. Finally, the amount of subtitling is reduced from full scripting to individual words and selected phrases in order to develop learners’ listening comprehension skills even more.

Thus, as can be observed in the proposal above, skillful use of captioning adds impact to the Business English course, enabling the teacher to adapt viewing comprehension tasks to the needs of the class depending on how difficult they may find the video extract.

7. Conclusion

Audiovisual translation, formerly restricted to translators with sophisticated and

expensive movie editing software and subtitling translation skills, has become much

more accessible to language teachers worldwide. Depending on the technical expertise

and experience in producing video captions, various kinds of technical solutions

can be used free-

Once such materials are produced, LSP instructors are free to choose from among different

implementation setups, ranging from teacher-

The area of enhancing foreign language instruction with subtitled video materials

is a relatively new one, and it needs both carefully controlled experimental studies

and practical small-

Acknowledgements

1. I am indebted to two anonymous reviewers, whose insightful comments helped refine the paper to its present shape.

2. I would like to dedicate this article to the fond memory of the late Andrzej Antoszek, Ph.D., who introduced me to the realm of audiovisual translation and whose sudden death interrupted our collaboration on subtitling projects.

References

Allan, M. (1985). Teaching English with Video. London: Pearson Longman.

Baltova, I. (1999). Multisensory language teaching in a multidimensional curriculum:

The use of authentic bimodal video in core French. The Canadian Modern Language Review,

56(1), 32-

Bird, S. A. and J.N. Williams (2002). The effect of bimodal input on implicit and

explicit memory: An investigation into the benefits of within-

Çakır, İ. (2006). The use of video as an audio-

Danan, M. (1992). Reversed subtitling and dual coding theory: New directions for

foreign language instruction. Language Learning, 42(4), 497-

Danan, M. (2004). Captioning and subtitling: undervalued language learning strategies.

Meta: Translators' Journal, 49(1), 67-

Gajek, E. (2008). Edukacyjne znaczenie napisów w tekście audiowizualnym. Przekładaniec,

20, 106-

Garza, T. J. (1991). Evaluating the use of captioned video materials in advanced

foreign language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 24(3), 239-

Guillory, H. G. (1998). The effects of keyword captions to authentic French video

on learner comprehension. CALICO Journal, 15(1-

Harmer, J. (2001). The Practice of English Language Teaching. London: Pearson Education.

Harmer, J. (2004). How to Teach Writing. Harlow: Longman.

Hedge, T. (1988). Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karakas, A. and A. Saricoban (2012). The impact of watching subtitled animated cartoons

on incidental vocabulary learning of ELT students. Teaching English with Technology,

12(4), 3-

Krajka, J. (2006). Developing speaking skills in a web-

Krajka, J. (2007). English Language Teaching in the Internet-

Kroll, B. (1991). Teaching writing in the ESL context. In: Celce-

Lonergan, J. (1984). Video in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Markham, P. L. (1993). Captioned television videotapes: Effects of visual support

on second language comprehension. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 21(3),

183-

Markham, P. L. (1999). Captioned videotapes and second-

Neuman, S. B. and P. Koskinen (1992). Captioned television as comprehensible input:

Effects of incidental word learning from context for language minority students.

Reading Research Quarterly, 27, 94-

Stempleski, S. and B. Tomalin (2001). Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, G. (2005). Perceived processing strategies of students watching captioned

video. Foreign Language Annals, 38(3), 422-

White, R. and V. Arndt (1991). Process Writing. Harlow: Longman.

Winke, P., Gass, S., and T. Sydorenko (2010). The effect of captioning videos used

for foreign language listening activities. Language Learning and Technology, 4(1),

65-

Yüksel, D. and B. Tanrıverdi (2009). Effects of watching captioned movie clips on

vocabulary development of EFL learners. The Turkish Online Journal of Educational

Technology, 8(2), 48-

Scripta Manent Vol. 8(1)

» Contents

» J. Krajka

Audiovisual Translation in LSP – A Case for Using Captioning in Teaching Languages for Specific Purposes

» P. A. Fuertes-

The Literal Translation Hypothesis in ESP Teaching/Learning Environments

Previous Volumes

(CC) SDUTSJ 2013. The Scripta Manent journal is published under Creative Commons

Attribution-