Home | Call for Papers | Submissions | Journal Info | Links |

Journal of the Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

ISSN: 1854-

Pedro A. Fuertes-

International Centre for Lexicography, University of Valladolid

Carmen Piqué-

Department of English and German Philology, University of Valencia

The Literal Translation Hypothesis in ESP Teaching/Learning Environments

ABSTRACT

Research on the characteristics of specialized vocabulary usually replicates studies

that deal with general words, e.g. they typically describe frequent terms and focus

on their linguistic characteristics to aid in the learning and acquisition of the

terms. We dispute this practise, as we believe that the basic characteristic of terms

is that they are coined to restrict meaning, i.e. to be as precise and as specific

as possible in a particular context. For instance, around 70% of English and Spanish

accounting terms are multi-

Keywords: Literal translation hypothesis, specialized texts, cognitive linguistics, ESP teaching, ESP learning.

1. Introduction

Nation (2001, 2006) and Laufer and Nation (1995, 1999) have investigated how much vocabulary typically needs to be learned in a foreign language at each stage of proficiency. They have claimed that second language learners do not need to know a very large quantity of words during the first stages of the learning process (e.g. Laufer and Nation, 1995, 1999). This view may not apply in ESP teaching/learning environments, as ESP courses typically target experienced language students, i.e. students who have been learning English for several years before entering tertiary education, e.g. eight years in Slovenia (Jurković, 2007) and similar figures in other European countries. This means that ESP teaching/learning environments are usually environments for intermediate to advanced students, i.e. environments in which learners must use a larger stock of words or terms for both the reception and the production of English specialized texts (Sarani and Sahebi, 2012).

Nation and colleagues (as well as many researchers working in the field of ESP) seem to have taken for granted that the process of learning general words, i.e. words that usually crop up in texts dealing with general matters, is similar to the process of learning technical words or terms, i.e. words that have a specific meaning or use in a particular domain (Chung and Nation, 2003, 2004). Gajšt summarises this view in relation to the use of corpus data for teaching purposes:

A common feature of corpus-

This paper disputes the above claims, which are usually based on incidental evidence.

For instance, Fuertes-

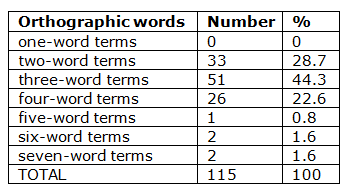

Table 1: Method terms in the English-

Some examples:

two-

three-

four-

six-

Table 1 shows that more than 70% of the English terms present in the specialised

domain of accounting, are typically composed of three or more orthographic words.

These are difficult, most of them impossible, to spot with existing technologies

that extract corpus data, as these are only reliable when searching for terms composed

of one or two orthographic words. This may be the reason that scholars usually only

report the working of multi-

The first implication is that extracting corpus data for use in ESP teaching and learning environments may not be highly recommended, as it will only address a small part of the vocabulary stock present in a specialized domain. The second implication is that we need more than corpus data for investigating how learners deal with terms. This approach must take into consideration that ESP learners are very different from other learners, e.g. high school students in a typical language learning environment.

Most ESP learners know, or should know, the factual characteristics of terms, as these are typically used in the subject field in which they are enrolled. For instance, Spanish students of Business English should know the encyclopaedic/semantic characteristics of most Business English terms before coming into contact with them. These should have been learnt in their specific subjects and therefore we can use this situation for upgrading the learning process, e.g. making use of the literal translation hypothesis described in this paper.

We believe that terms enter into a domain through different methods of term formation, the literal translation being the one we focus on in this paper. If we can demonstrate the plausibility of a literal translation hypothesis (section 2 below), then we can (and must) take into consideration the existence of a drive for verbatim translations that will be present in our students' minds. In other words, if students of a particular ESP program are inclined to form verbatim translations of English terms, then we will approach the teaching and learning of ESP terms in a way that is different from the approaches typically described in the literature on ESP learning, which are often based on corpus data, i.e. on the existence of frequent patterns.

The plausibility of a literal translation hypothesis is investigated (Section 2) and its implications examined in a pilot study (Section 3). The results obtained are discussed (Section 4), with a view to offering some recommendations for teaching English terms to foreign learners (Section 5). A final conclusion summarises the main ideas discussed.

2. The literal translation hypothesis

To understand the “nature of semantic differences between words and their apparent

translation equivalents in different languages” Croft and Cruse (2004: 19) use the

profile/frame domain distinction. According to them, a profile refers to the concept

symbolized by the word in question, whereas a frame or domain is any system of concepts

related in such a way that to understand any one of them one has to understand the

whole structure in which the concept fits (Fillmore, 1982). This distinction may

explain the existence of culture-

Without taking into account the existence of cultural differences in specialized

domains, recent research in the field of specialized lexicography has signalled the

existence of several forces that contribute to diminishing such differences. For

instance, Fuertes-

The introduction of acción fantasma into Spanish is an example of a new term that

enters the language as a verbatim translation of English phantom share. This novel

metaphor was introduced into Spanish by the compilers of the above-

The maintenance of conceptual affinity, as well as the difficulty that professional translators and students of ESP have to understand some concepts when dealing with specialized texts, offers ground for hypothesizing that both translators of specialized texts and students of ESP are primed for accepting verbatim translations of terms, e.g. terms originally coined in English.

This priming for verbatim renderings has been explored by translation scholars (Baker,

2001), and by researchers concerned with analyzing the role of similarity and frequency

in the bilingual mental lexicon. For example, Levelt (1989), Lowie, (1998), and Lowie

& Verspoor (2004), among others, have investigated the so-

Secondly, the priming for literal translation renderings has an effect on both the

conceptual scenarios and the discourse of the target language. Identity of conceptual

scenarios leads to eliminating cultural differences, as do borrowings and loans

in specialized texts. This means that experts are so familiar with working with texts

written in a lingua franca, e.g. English, that they copy this language without questioning

this practice. For instance, on October 30, 2011, a well-

The absence of reaction may be connected with a new trend (not-

3. The pilot study

This section describes a pilot study carried out to shed light on some of the cognitive processes taking place during the act of working with foreign language texts and to offer arguments in support of the literal translation hypothesis.

The pilot study has the role of a “laboratory” for a follow-

The pilot study consists of three steps. Firstly, we have chosen a translated specialized

text from English into Spanish that was published in a daily newspaper. The text

chosen was published on February 14 2010, and was included in the economy supplement

of El País, a Spanish daily that is widely circulated in Spain, especially on Sundays.

The selection of a text published in a well-

The second step rests on the assumption that texts published in the economy supplement

of a national daily are frequently read only by experts, semi-

The concept of natural language is used as a proxy for literalness. A natural language

is the language that arises in an unconscious way and is typically produced and understood

by native speakers in an unpremeditated fashion (Lyons, 1991). In this paper, this

concept assumes that the respondents’ subjective responses when asked to identify

instances of disjoint syntax, loans, and lack of idiomaticity will be very much influenced

by some combination of background knowledge, experience, and nativeness (Fuertes-

· Readers familiar with the topic (economic issues in this text) will only consider

unnatural gross translation mistakes. The explanation for this is that Spanish experts

are used to reading English economic texts and making automatic ad-

· Readers unfamiliar with the topic but used to translating regularly will consider

unnatural instances that contain translation mistakes and some translation solutions

(Fuertes-

· Readers unfamiliar with the topic and with English, but who teach Spanish and know

rules and prescriptive norms will find unnatural instances of translation mistakes

and many more instances of syntactic errors (Fuertes-

The third step consists of selecting informants according to their level of background knowledge and experience in business/economics, translation from English into Spanish, and Spanish grammar. We selected 15 respondents, distributed into groups of five, and asked them to read the text and underline instances of what they perceived as unnatural Spanish.

Group 1 (G.1) was formed of five Spanish professors of business/economics who are used to reading texts published in the economy supplement of national dailies, especially those written by Nobel Laureates as the one chosen in this pilot study. Five Spanish professors of English, who read English texts regularly, sometimes translate into Spanish, but tend to skip the supplement, formed the second group (G.2). Group 3 (G.3) was formed of five Spanish professors of the Spanish language who read English occasionally and with difficulty but have never translated English texts into Spanish or Spanish texts into English. All these 15 respondents were Spanish professors at the University of Valladolid, i.e. educated native speakers. They were briefed on the task to be carried out and instructed as follows:

1. You will receive an anonymous Spanish text.

2. Please read the text (it will take around 10 minutes).

3. Once you have read the full text, please underline words, phrases or sentences that sound like unnatural Spanish.

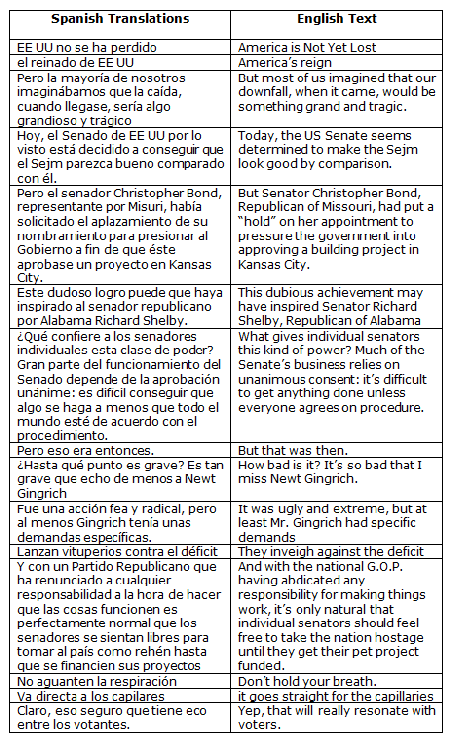

Once the participants completed the task, we selected the translations that occurred three or four times as we believe that they are representative of trends. These were presented alongside their English originals (Table 2) and identified by group (Table 3).

Table 2. Instances of Unnatural Spanish and their English Original Counterparts.

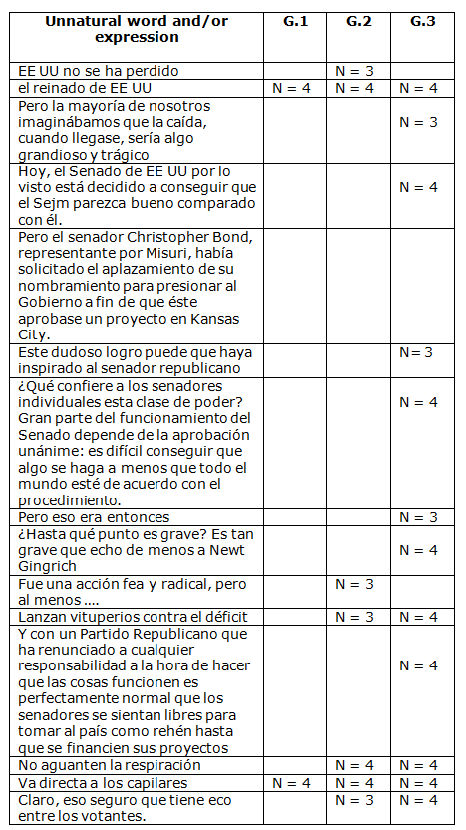

Table 3: Instances of unnatural Spanish identified by the three groups of informants

4. Discussion

The following discussion offers our explanation for the data reported in Table 1. As expected, respondents in G.1 only found two instances of unnatural Spanish: “el reinado de EE UU” and “va directa a los capilares”. Both are inappropriate translations and easily detectable (respondents in G.2 and G.3 also report them as ‘unnatural’: It is common knowledge in Spain that the United States is not a kingdom (reinado) and that the idiomatic expression is “va directa a la yugular”, not to the “capilares” (“capilar” in Spanish refers to ‘hair’).

As expected, respondents in G.3 found many examples of unnatural Spanish, which we explain as instances of syntactic calquing, i.e., sentences that are formed according to the syntactic rules of English, and which are presented as examples of Anglicism in Spanish prescriptive grammars:

· “Pero la mayoría de nosotros imaginábamos que la caída, cuando llegase, sería algo grandioso y trágico”: The translation of when it came and its place in the middle of the sentence is unnatural Spanish according to Spanish rhetorical tradition. In addition, “grandioso” and “trágico” are wrongly inflected. They should be feminine (“grandiosa” and “trágica) as they go with the feminine noun “caída”. And when it came refers to a hypothetical fact and therefore should have been translated as conditional and placed before or after the main clause.

· “Hoy, el Senado de EE UU por lo viso está decidido a conseguir que el Sejm parezca

bueno comparado con él”: in this case the ordering, wording and syntactic arrangement

are ‘unnatural’. Instead of “hoy” Spanish-

· “Este dudoso logro puede que haya inspirado al senador republicano por Alabama Richard Shelby”: the presence of the “that clause”, and the lack of a relative clause referring to Richard Shelby are ‘unnatural’ in Spanish.

· “¿Qué confiere a los senadores individuales esta clase de poder? Gran parte del funcionamiento del Senado depende de la aprobación unánime: es difícil conseguir que algo se haga a menos que todo el mundo esté de acuerdo con el procedimiento”: The use of a rhetorical question followed by its answer is unnatural Spanish, as is the word order and syntactic arrangement.

· “Pero eso era entonces.” This case is unnatural for rhetorical reasons. In natural written Spanish such sentences are considered colloquial and instances of disjoined syntax. They are somehow connected with previous or following sentences.

· “¿Hasta qué punto es grave? Es tan grave que echo de menos a Newt Gincrich”. The initial rhetorical question is not used in natural Spanish. As this is used for emphasis, natural Spanish would have included a lexical booster, e.g. incluso.

· “Y con un Partido Republicano que ha renunciado a cualquier responsabilidad a la hora de hacer que las cosas funcionen es perfectamente normal que los senadores se sientan libres para tomar al país como rehén hasta que se financien sus proyectos”: In this case the theme/rheme structure, especially the initial “Y” and the presence of the prepositional phrase and a relative in initial position are all unnatural.

Respondents in G.2 consider the translation of “fea” and “radical” for “ugly and

“extreme” as ‘unnatural’. Both respondents in G.2 and G.3 identify three more instances

of unnatural Spanish: these three are incorrect translations of idiomatic English

expressions. The problems related with the translation of idiomaticy are well-

In sum, the pilot study here lends support to the premises upon which the working

of the literal translation hypothesis works in a semi-

As previously indicated, informants’ responses agree with the abovementioned assumptions

made. Firstly, the informants in G.1 did not identify unnatural instances as they

are familiar with making their own ad-

5. The implications of the hypothesis for learning English terms

Corpus-

The above objections cannot ignore that the corpus revolution has demonstrated the

validity of Sinclair's (1991) idiom principle, i.e., language users have access to

a number of semi-

1. Students, e.g. Spanish students enrolled in an ESP program, are primed for verbatim translations of unknown terms. This means that the transferring of meaning that any L2 teaching/learning process demands is not hampered if instructors offer L1 translations of L2 terms.

2. There are many instances of verbatim translations, perhaps because terms are always

restricted, i.e., they refer to particular places, methods, procedures, systems,

approaches, etc. This explains that most terms are never frequent and are therefore

undetected with corpus methodologies. In other words, contrary to Nation and colleagues'

conclusions (e.g. Chung and Nation, 2003, 2004), terms that are difficult to process

and disambiguate, i.e., the terms that are usually problematic for students, cannot

be identified through frequency counts; instead they must be enumerated individually

and worked with individually. This means that corpus work does not offer a linguistic

means to explore technical concepts and therefore a way to bridge the gap between

language knowledge and concept knowledge; instead, this gap can and must be bridged

through a combination of explaining facts, i.e., the concepts, and teaching language

features. We have followed this idea and have constructed dictionaries, e.g., the

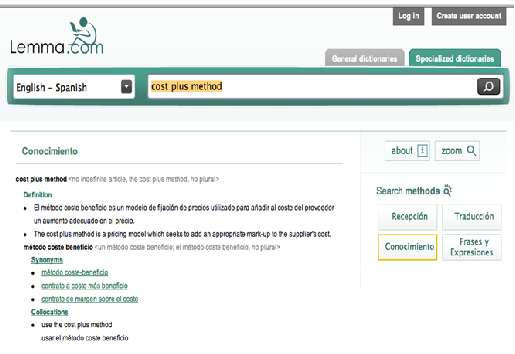

Diccionario Inglés-

a. Around 50% of terms contain three or more orthographic-

b. Multi-

Figure 1. Screenshot from the Diccionario Inglés-

Instead, we propose exercises in which students have to use real language, especially

multi-

To sum up, the existence of a literal translation hypothesis reinforces our view that ESP teaching/learning environments must reproduce what students practice when they are in their L1 teaching/learning environments. Or to put it in another way, assuming that ESP students are primed for literal translations, ESP instructors can upgrade their activities with tasks that are similar to the activities students have already performed in their L1. A Spanish student of Business is never asked to “make guesses”, but to understand the real meaning of a text. This is what we wish to achieve in an ESP teaching/learning environment.

6. Conclusion

This paper has presented the plausibility of the literal translation hypothesis that

assumes that other factors being equal, students are primed for verbatim renderings

of L2 terms, especially multi-

If proved correct, the tenets of the above hypothesis will demand more than corpus

data for teaching and learning ESP. For instance, recently conceived dictionaries

such as the Diccionario Inglés-

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are due to the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on a previous draft of this article.

1 The dictionaries are: Diccionario de Términos Económicos, Financieros y Comerciales (Alcaraz y Hughes, 2008); Diccionario LID Empresa y Economía (Elosúa, 2007).

References

Baker, M. (2001). Issues in Translation Research and Their Relevance to Professional

Practice. The Journal of Translator Studies 2 (1), 99-

Chung, T.M. and Nation, P. (2003). Technical Vocabulary in Specialised Texts. Reading in a Foreign Language, 15(2). [online]. Available: http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/RFL/October2003/chung/chung.html (20 May 2013).

Chung, T.M. and Nation, P. (2004). Identifying Technical Vocabulary. System, 32(2):

251-

Croft, W. and Cruse, D. (2004). Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Curado-

Fillmore, C. (1982). Frame Semantics. Linguistics in the Morning Calm. Ed. The Linguistic

Society of Korea, 111-

Fuertes Olivera, P. A. (1998). Metaphor and Translation: A Case Study in the Field

of Economics”. In Fernández Nistal, P. & Bravo, J. M. (Eds.): La traducción: orientaciones

lingüísticas y culturales. Valladolid: University of Valladolid, 79-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Fuertes-

Gavioli, L. (2005). Exploring Corpora for ESP Learning. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Gajšt, N. 2013: Technical Terminology in Standard Terms and Conditions of Sale: A

Corpus-

Jurković, V. (2007). Vocabulary Learning Strategies in an ESP context. Scripta Manent

2(1), 23-

Laufer, B. and Nation, P. (1995). Vocabulary Size and Use: Lexical Richness in L2

Written Production. Applied Linguistics 16 (3), 307-

Laufer, B. and Nation, P. (1999). A Vocabulary-

Levelt, W. J. M. (1989). Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge, Mass: Bradford.

Lowie, W. M. (1998). AIM: The Acquisition of Interlanguage Morphology. PhD Dissertation. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit.

Lowie, W. M. and Verspoor, M. (2004). Input versus Transfer? The Role of Frequency

and Similarity in the Acquisition of L2 Prepositions. In Michel Achard and Susanne

Niemeier (Eds.) Cognitive Linguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Foreign Language

Teaching. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 77-

Lyons, J. (1991). Natural Language and Universal Grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning Vocabulary in Another Language. Cambridge University Press).

Nation, P. (2006). How Large a Vocabulary Is Needed for Reading and Listening. The

Canadian Modern Language Review 63(1), 59-

Nida, E. (1964). Towards a Science of Translation. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

Sarani, A. and Sahebi, L. F. (2012). The Impact of Task-

http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/elt/article/view/19956/13159 (June, 5, 2013).

Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, Concordance, Collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1978). Teaching Language as Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widdowson, H. G. (1998). Context, Community, and Authentic language. TESOL Quarterly

32(4): 705-

Scripta Manent Vol. 8(1)

» Contents

Audiovisual Translation in LSP – A Case for Using Captioning in Teaching Languages for Specific Purposes

» P. A. Fuertes-

The Literal Translation Hypothesis in ESP Teaching/Learning Environments

Previous Volumes

(CC) SDUTSJ 2013. The Scripta Manent journal is published under Creative Commons

Attribution-