Home | Call for Papers | Submissions | Journal Info | Links |

Journal of the Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

ISSN: 1854-

Melita Koletnik

Expanding Vocabulary Through Translation – An Eclectic Approach

ABSTRACT

Owing mostly to the overwhelming tide of a communicative approach in foreign language

teaching, translation was widely excluded from language classes for much of the 20th

century. Nevertheless, translation never went away completely; it patiently waited

for a time when the language teaching community would again discover synergies between

translation and established approaches, thence reassess its lost potential. As is

established herein, such potential is at its greatest and most effective in relation

to vocabulary, where -

This paper, building on the theoretical and methodological frameworks, together with the author’s own classroom observations, reassesses the role of translation and proposes a set of activities which could be used by teachers of English for specific purposes and translator trainers alike. It concludes with a recommendation as to the universal applicability of translation, especially in the context of languages for specific purposes and translator training.

Keywords: translation, vocabulary, grammar-

1. Introduction

For much of the 20th century, use of a student’s first language as well as translation

were largely excluded from language for specific purposes (LSP) teaching, translation

training and general foreign language classes. This was for the most part due to

the overwhelming tide of the communicative approach which rejected and replaced the

centuries-

My hitherto experience in foreign language teaching (FLT) at BA and MA levels has

involved various applications of translation using both the students’ native language

(Slovene -

Through a review of FLT and translation theory, I have drawn on the following types of materials:

1. handbooks, theoretical and methodological guides to general foreign language teaching,

focusing mostly on the English language (e.g. Hedge 2003, Larsen-

2. theoretical monographs and articles on specialised language teaching (Harding 2007, Hutchinson and Waters 1996) and,

3. theoretical and practical literature on translation in language teaching (e.g. Cook 2010, Malmkjaer and Williams 1998, and Duff 1994).

The methodological approaches are supplemented by my own classroom experience and observations.

2. Theories

Owing to the overwhelming tide of communicative approaches during much of the 20th

century, use of students’ L1 -

Within the context of the grammar-

The communicative approach, as the method which replaced grammar-

Despite addressing and contributing to the introduction of some undoubtedly important

aspects of the language learning process, such as the use of authentic materials

and real-

One of the areas of FLT where a “natural” use of translation seems most apparent

is the acquisition of new vocabulary. It is my firm belief that every teacher applying

a monolingual approach can report at least one instance when -

As reported from the FLT classroom, as well as in the literature of some FLT authors,

e.g. Hedge in 2003, vocabulary has long been subject to neglect; this is quite surprising,

especially when one considers that “errors of vocabulary are potentially more misleading

than those of grammar” (Hedge 2003: 111). Such can, however, be explained by the

fact that the task of vocabulary learning is substantial, permanent and on-

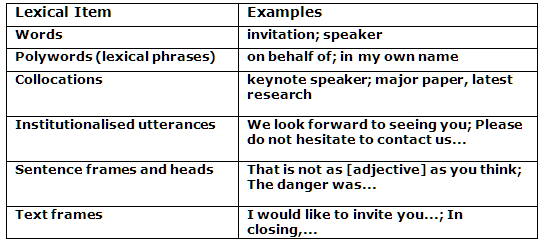

For purposes of clarity, I would add that herein “vocabulary” should be understood

not solely as individual lexical items or words, but also of multi-

Table 1: Taxonomy of Lexical Items (Lewis, 1997)1

Combining communicative and lexical theories with the proven benefits of grammar-

3. Materials Selection

Vocabulary has always been very present in the classes I taught as a teaching assistant

at the University of Maribor, Slovenia, be it as part of the general ELT tutorials

(English Language Development I and II taught to first and second year students)

or specialised tutorials focusing on translation (Translation I, II and III taught

to second and third year students). While the acquisition of vocabulary has already

been a learning objective incorporated within the English Language Development syllabus,

the need to further develop students’ vocabulary as part of the Translation I, II

and III has arisen from personal experience and the quest for natural language learning,

as well as from students’ positive responses to activities involving different vocabulary

item-

The materials presented further herein were devised for the Translation II tutorials

taught to third year students of Interlingual Mediation at Maribor University’s Department

of Translation Studies. In terms of materials selection, the syllabi of Translation

II and III tutorials were co-

The main criterion for the selection of materials was their representativeness within

a given text type, followed by naturalness of expression and overall correlation

with the intended learning objectives. The materials were either located on-

4. Method

The text, a letter of invitation, was presented to students in the scope of an overall

focus on business and diplomatic correspondence, constituting a part of the functional

stylistic category of official documents. During the previous lesson, students had

been presented with business letters and typical communicative situations where such

letters are used, written and translated; and we continued with a related text. Much

care was taken that students took a central role in the activities; the teacher’s

role should be limited to solely that of a guide and facilitator in the creation

of a productive learning environment for pro-

First, students were asked to read the text in English (L2), and, while reading, to focus on highlighted chunks of vocabulary4, reflect on them and find a way of expressing the same concept in Slovene (L1)5. They were not given a parallel text in L1 at this point of time because the task was aimed at activating their existing vocabulary, a goal which was achieved effectively. The subsequent discussion produced some more or less successful suggestions, which ranged from literal translations to fully functional equivalents capable of meeting the expectations of a Slovene native speaker.

Table 2: Examples of preliminary translation solutions

The selection of this particular text also promoted the discussion of selected aspects

of L2 grammar, namely, the sequence of adverbials at the end of the sentence (manner,

place, time) which usually differs in Slovene (where time is before place) and punctuation

(American vs. British English punctuation, open punctuation, etc.). It should be

added that vocabulary was addressed only to the extent in which it was relevant for

the discussed text-

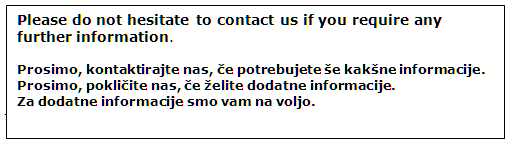

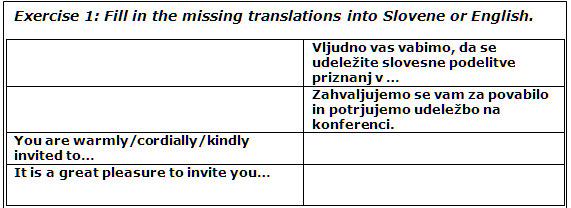

Next, students were presented with two sample texts in L2 and L1 for further reference

as well as a list of “useful expressions” based on the examples provided in the textbook

by M. Lipec (2002) discussing Slovene and English business and diplomatic correspondence.

The list was partially blanked out and the students were asked to complete -

Table 3: Exercise 1 with examples of “useful expressions” (adapted from Lipec, 2002)

During their search for appropriate collocations, students were informed that they

might resort to use of the on-

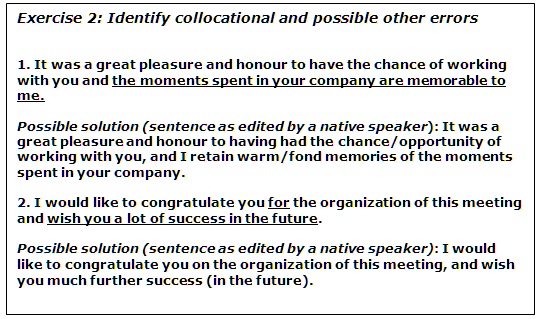

The next activity involved the use of a small number of larger lexical units, namely selected sentences translated into L2 by L1 speakers. These examples were taken from the book by A. McConnell Duff (2000). Students were asked to identify collocational and other possible errors made by the translator (e.g. faulty use of prepositions) or to rephrase the sentence in order that it remains as close to natural L2 expression as possible.

Table 4: Exercise 2 with examples of sentences to be corrected (adapted from Duff, 2000).

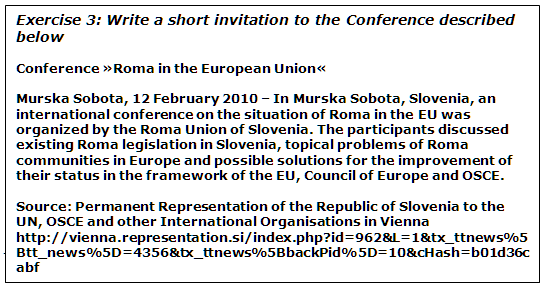

Next, in order to activate their productive knowledge, students were asked to write

an invitation to a real-

Table 5: Exercise 3: A short informal invitation to the Conference

Finally, as a homework assignment, students were asked to use a dictionary to find frequent collocations with the following words: provisional, to invite, and speaker. The collocations could use the words literally or metaphorically and should involve different parts of speech combination (e.g. verb + noun, verb + adverb, adjective + noun, adverb + adjective, etc.). The submitted collocations were collected by the teacher and presented to them collectively during the next hour in the form of a mind map. As the final part of this class, students were asked to prepare a translation of the sample letter of invitation and submit it for evaluation.

5. Conclusions

The proposed FLT approach, with its focus on vocabulary, natural expression and bidirectional

translation, is a step away from the monolingualism postulated by communicative language

teaching. Despite having arisen from personal observations and classroom situations,

it finds sound footing in the considerations of FLT theoreticians. Through a variety

of carefully selected exercises, as well as through the use of authentic language

and situations, this approach likewise promotes some of the core principles of communicative

language teaching, namely authenticity and genuine context; whilst through its highlighting

the central role of vocabulary in L2 acquisition it is supportive of lexical teaching.

Lastly, but by no means least, this application re-

On the basis of student feedback, and their success in exam situations, as well as from animated classroom discussions, such exercises have proven successful in promoting student knowledge as well as the attainment of set learning objectives. I am, however, aware that at present no concrete data exists which would scientifically corroborate my personal conclusions in any satisfactory manner. It is therefore my desire and intention to submit the proposed approach so that it may be further scrutinised by interested academicians and practitioners. I believe the approach described herein is universally applicable; it has been used with much success in translator training involving specialised texts, and it is my desire that it be implemented in further LSP and translator training contexts

1 http://coerll.utexas.edu/methods/modules/vocabulary/02/lexical.php

2 The functional styles (genres) are understood as types of texts with distinctive linguistic and stylistic characteristics, and are classified according to different communicative settings.

3 This same letter is available at: http://businesscommunicationletters.blogspot.com/2007/04/invitations.html

(a website offering samples of English business correspondence), as well as http://www.ecasd.k12.wi.us/faculty/shaslow/business_letters_and_logo_samples.pdf

(a school in Wisconsin, USA), or http://www.invitation-

4 Such institutionalized utterances would be frequently referred to as formalised or standardised expressions.

5 Frequently, the students would be challenged by a question: »How would we put

it?« or »How would they say…?« emphasizing the importance of native-

6 http://5yiso.appspot.com/search

7 e.g. BNC and COCA for English, and FidaPlus and Nova beseda for Slovene

8 The asterisk or a star (*) is a placeholder for any unknown item in a query and produces results based on the frequency of appearance of this item.

References

British National Corpus, BNC [online]. Available: http://natcorp.ox.ac.uk (25 April 2012).

Carreres, A. (2006). Strange Bedfellows: Translation and Language Teaching. The teaching of translation into L2 in modern languages degrees; uses and limitations [online]. Available: http://www.cttic.org/ACTI/2006/papers/Carreres.pdf (12 December 2011)

Cook, G. (2010). Translation in Language Teaching: An Argument for Reassessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) [online]. Available: http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/Source/Framework_EN.pdf (25 April 2012)

Corpus of Contemporary American English, COCA Available: http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/ (25 April 2012)

Duff, A. (1994). Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FidaPlus, Korpus slovenskega jezika [online]. Available: http://www.fidaplus.net (25 April 2012).

Harding, K. (2007). English for Specific Purposes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hedge, T. (2003). Teaching and Learning in the Language Classroom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hutchinson, T and A. Waters (1996). English for specific purposes: a learning-

Larsen-

Lewis, M. (1997). Implementing the Lexical Approach: Putting Theory into Practice. Andover, Hove: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Lipec, M. (2002). Priročnik Poslovne in Protokolarne Angleščine. Ljubljana: Mladinska Knjiga.

Malmkjaer, K. and J. Williams [eds.](1998). Context in Language Learning and Language Understanding. Cambridge [etc.]: Cambridge University Press.

McConnell Duff, A. (2000). Into English: Writing and Translating into English as a Second Language: A Practical Guide to Recurrent Difficulties. Ljubljana: DZS.

Nova beseda, Besedilni korpus pri ZRC SAZU. Available: http://bos.zrc-

Oxford Dictionary of Collocations [online]. Available: http://5yiso.appspot.com/ (25 April 2012).

Appendix

August 15, 2006

Mr. Roger Moriarity

Executive Director

Children With Disabilities Foundation

430 Smithson

Drive, Suite 500

Chicago, IL 32956

Dear Mr. Moriarity:

I would like to invite you, on behalf of the Board of Directors

and in my own name, to be the closing keynote speaker at the upcoming 2006 IDCRI

Conference.

The theme of this conference is "Disabling the Disability -

I would like to inform you that Susan

Crutchlow of Taming the Environment will be the opening keynote speaker. The provisional

title of her presentation is "The Disabled Environment -

We expect

attendance this year to be the highest ever; in the area of 2,000 delegates and 150

speakers. This includes a large contingent from our new European Chapter that is

based in Geneva. You may have heard that Dr. Walton Everinson will be presenting

a major paper on his latest research into "Genetic ReEngineering". We are already

receiving inquiries from all over the world about Dr. Everinson's presentation.

In

closing,

I will call you in a week or so to follow up on this. Please do not hesitate to contact

us if you require any further information.

Yours sincerely,

Richard Bagnall

Executive Director

International Disabled Children Research Institute

© 2005-

Scripta Manent Vol. 7(1)

» Contents

» M. Koletnik

Expanding Vocabulary Through Translation – An Eclectic Approach

Anglizismen im berufsbezogenen

DaF-

» J. Skela

English for Theologians, by Urška Sešek and Simona Duška Zabukovec

Review

Previous Volumes