Journal of the

Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

Journal of the

Slovene Association of LSP TeachersISSN: 1854-2042 |

|

|

Home | Call

for Papers | Submissions | Journal

Info | Links | |

Inna Kozlova

Studying Problem Solving through Group Discussion in Chat Rooms

In the present article we use a chat conversations’ corpus to study the process of resolving language problems. Our corpus includes chat conversations which took place between LSP students engaged in correcting errors in their peers’ summaries. The participants worked in groups and used the Windows Messenger program for communication within the group. Their task also included making use of electronic dictionaries and other reference materials. The conversations’ corpus obtained as a result of this exercise was analyzed holistically for possible indicators of each particular stage of the problem solving process. Later these indicators were validated throughout the entire corpus. Each problem solving process was thus represented as a chain of indicators and acceptability was determined for each error correction. The resulting problem solving chains were used to prove our hypotheses concerning internal and external support in text reproduction.

Key words: LSP, chat, problem solving, dictionaries, error correction, reference.

1. Introduction

Recent studies into external reference sources such as dictionaries are progressively shifting into the realm of psycholinguistics. There is no doubt that an external reference sources’ query has to be viewed in a global context for the problem to be solved. Internal support thus becomes only one part of the problem-solving process; external support being the other part, which acquires especial importance in LSP context. To measure the scope of each type of support, we designed a study where problem solving could be recorded and later analyzed. For this purpose, we gave our students an online writing task consisting of correcting mistakes in groups.

Orlando Kelm (1992) found that realtime computer-assisted class discussions “promote increased participation from all members of a work group, allow students to speak without interruption, reduce anxiety which is frequently present in oral conversations, render honest and candid expression of emotion” (p. 441). Moreover, the substantial volume of its output makes it possible to provide a personalized identification of target language errors (ibid.) and offers a wide range of possibilities for error correction. The database of online writing can be used by the teacher for meta-cognitive reflection that can raise students’ awareness of the linguistic, organizational and rhetorical choices available to them (Sengupta, 2001; Yuan, 2003).

In our study, the computer is used first as a means of communication between the study participants; second, it makes it possible for us to create a database of digitally recorded written conversations, which allows for subsequent corpus analysis; third, the virtual environment provides our participants with access to electronic dictionaries and auxiliary texts, both on and offline.

We bore in mind that the virtual environment is notorious for creating false expectations in students, as students’ individual efforts tend to decrease as they rely more on technology. In particular, we took into consideration Chelly Vician and Susan Brown’s (2000) recommendation to carefully craft writing assignments to bring them in line with their intended outcomes, as student discourse online tends to be closely linked to fulfilling the assignment according to the instructions. We provided our study participants with detailed instructions, not only in order to provide a consistent outcome but also to avoid possible technical problems in the course of the exercise.

2. The study

2.1. Study participants and their preparation

Fifty university ESP students of English for Social Sciences with Political Science as their major and Spanish and/or Catalan as their mother tongue participated in the study. The course is obligatory for second-year students who are split into two groups depending on their language proficiency; ours is the lower level. Our students had received no particular training in online dictionary skills. However, almost all of them seemed to be acquainted with the Windows Messenger program, which they reported to use in their daily routine.

During the 2nd semester our students worked in groups of three or four on a particular socially problematic issue. The students had to use three original English articles as a source of lexical and factual information about their topic. The project included an oral presentation, which was followed by a general debate in class organized by the group. Finally, each group delivered a summary of their presentation to the teacher in electronic form, which included a list of 20 new vocabulary items with corresponding context translations and hyperlinks to the three background articles also enclosed in the summary. We believed that such a detailed preparation would make students demonstrate their maximum linguistic competence while working on their summaries. The presentation in class and the debate were aimed at balancing linguistic and conceptual knowledge among the students, at least for the given topic. All the students in class received handouts including information on the established social issue and vocabulary which were prepared by the organizing group.

2.2. Texts and their preparation

The texts to be corrected by the participants were chosen from the summaries handed in by the students as part of their semester project. Each summary focused on a specific topic, was approximately 250-300 words long and based on three background articles written in English. The summaries were analyzed by the teacher who marked ten errors in each of them. These errors were to be corrected by the participants in the course of the final task. While choosing the type of teacher's feedback we took into account the studies of Dana Ferris (2002) and Thomas Robb et al. (1986) who claim that students learn more and make fewer errors in the future if they identify and correct their errors by themselves, in contrast to the situation when it is the teacher who corrects them. Jean Chandler (2003) observes that teacher’s feedback which consists of marking mistakes appears to be more effective than labeling them indicating the type of the error. In addition to saving teacher’s time, ‘marking-only’ arouses students’ curiosity and makes them look for the origin of the mistake, which has a positive effect on learning results.

Taking into account the fact that when preparing their summaries the students had already demonstrated their maximum linguistic (and probably also instrumental) skills, it was within the teacher’s competence to indicate the errors that were still present in the summaries. The errors we marked are theoretically possible to correct with the help of resources available during the task. We checked that the electronic dictionary installed on the hard disk of the computers contained answers to the majority of the problems, were they orthographical, lexical or combinatorial. We marked the whole segment affected by the mistake where at least some part had to be corrected. To give an example, in the sentence “Frequently, this harassment affect to women…” the segment “affect to” is marked to be changed into “affects”, while in “USA attacks” “USA” is marked for the definite article to be added. This kind of marking responds to our idea that querying the corresponding dictionary entry or a search through auxiliary texts would help students to solve the problem.

2.3. The task

The final part of the project took place in a computer classroom where the students have to correct one of the aforementioned summaries. Again, the students had to work in groups, each group on a different summary assigned to them. The distribution into groups was ideated previously by the teacher. We created Messenger accounts for each computer according to its serial number and arranged them into groups of six or seven choosing the computers situated physically farthest from each other. Thus we organized a distribution where the students who had to work on the same text found themselves in different classroom locations, so the only way they could communicate was through writing. All the conversations were thus carried out using the Messenger 5.0 program and each group record included the total of the group conversations.

The task we offered our students consisted of error correction in texts. For this reason we speak of this exercise as a variety of text reproduction, the term comprising any kind of text re-elaboration with a certain objective. Gert Rickheit and Hans Strohner (1989) refer to it as ‘Textverarbeitung’ or ‘Textreproduction’. Text reproduction includes both text comprehension and text production processes somehow related to each other. Both comprehension and production in foreign language, even when studied separately, prove to be complex mental processes. As long as one’s linguistic competence allows it, these processes are conducted automatically. As soon as a problem is identified, a local problem-solving process starts taking place. In text reproduction, this local problem may be related to the task of text reproduction or it may form part of either comprehension or production. In our study we attempted to both establish a relationship between the two processes and study each of them as parts of a global process.

2.4. Materials used in the task

The materials included:

- monolingual dictionary (Collins English Dictionary, 2000) installed on the hard disc of each computer;

- bilingual English-Spanish Spanish-English dictionary (Collins Spanish Dictionary, 2003) installed on the hard disc of some computers (one or two per group);

- access to the Internet in case participants wished to consult online dictionaries or other resources.

2.5. Task in progress

Each student joined a group after being invited to chat by the secretary. The students were informed about the location of the text and were able to visualize it on their screens though they could not correct it themselves. Then they were encouraged by the secretary to propose solutions to the problems underlined by the teacher. The “Instructions for Students” handout specified evaluation criteria. The students would receive their group grade (50 % of the total grade) as well as their individual grade (the other 50%). On one hand, we intended to promote collaboration within the group. On the other hand, the students were expected to demonstrate their initiative and use resources in a conscious way. The task took two classes 1h 30m, at the end of which the students filled out an optional questionnaire conceived to evaluate the profitability of this exercise.

2.6. Data and data collection method

The collected data consists of summaries corrected by corresponding groups of students (the product data) and group conversations where each problem-solving process was verbalized and recorded (the process data). The summaries corrected by the students were evaluated by the teacher from a normative perspective and each solution was classified as acceptable or unacceptable. As for the group conversations, these were analyzed by our own method based on corpus methodology. We decided to use this new method because the already existing methods, such as retrospection, introspection and direct observation, have serious shortcomings. Namely, retrospection would not give us access to working memory processes, and at the moment of verbalization a large part of the information would have been forgotten. Introspection, also known as a think-aloud protocol, would interfere with the problem-solving process of the participants making them behave in an unnatural way and thus breaching the ecological validity of the study. Direct observation was not possible in our case as many observers would be needed (at least one for each study participant) and their presence would certainly influence the participants’ behavior. Our own method allowed us to observe and analyze the problem-solving process. Broadly speaking, it consisted of the following:

b) saving these conversations in a digital format, thus creating a corpus for analysis,

c) looking for action indicators in the conversations corpus,

d) verifying action indicators in the whole corpus,

d) labeling our corpus, and

e) analyzing the resulting problem solving sequences in contrast.

2.7. Hypotheses

Placed in the context of text reproduction, our task embraced both text comprehension and text production. Our first hypothesis focused on discovering the order that comprehension and production, as parts of text reproduction process, should maintain. We hypothesized that comprehension should come first and production next in those problem-solving sequences that lead to acceptable solution of the problem. Hypothesis 1: For better results, comprehension should precede production.

The second hypothesis focused on studying internal support. We intended to verify whether a deeper cognitive implication, understood in our study as more intense internal support, is more characteristic of problem-solving sequences with acceptable results. Hypothesis 2: A deeper cognitive implication leads to better results.

The last hypothesis focused on external support as additional to internal support. We tried to confirm that a deeper search in reference sources, understood by us as more intense external support, is associated with problem-solving sequences with acceptable results. Hypothesis 3: A deeper search in reference sources leads to better results.

2.7.1. Action indicators as working hypotheses

To be able to verify our hypotheses, we needed indicators for: 1) comprehension and production processes, 2) the phases of internal support, and 3) the additional phase of external support. Having looked through the corpus of chat discussions, we hypothesized that such words as ‘understand’ and ‘mean’ usually make reference to comprehension, while ‘solution’, ‘change’ and ‘put’ are used to refer to production (see Processes in Table 1).

| PROCESSES |

INDICATORS |

| Comprehension (C) |

understand, mean(ing) |

| Production (P) |

solution, change, put |

| PHASES OF INTERNAL SUPPORT |

|

| Identification of a

problem (I) |

problem, don´t know |

| Definition of a problem (D) |

problem, don´t know |

| Generation of possible

solutions (G) |

think,

maybe/possible/could be, can |

| Evaluation of possible

solutions (E) |

better, is (not) correct |

| ADDITIONAL PHASE OF EXTERNAL SUPPORT |

|

| Resources use (R) |

dictionary, bilingual,

Collins, Google, Altavista, translator |

Table 1: Indicators of processes and problem-solving stages as working hypotheses

Problematic processing, both in comprehension and production, requires internal and sometimes external support. To determine the phases of internal support, we used Robert Sternberg’s (1996) Problem-Solving Cycle model as a basis. We also studied the processes of comprehension and production, which helped us to distinguish four main phases of internal support common to both comprehension and production (see Phases of Internal Support in Table 1): identification of a problem, its definition, generation of possible solutions and their evaluation. We observed that ‘problem’ and ‘don’t know’ were used by the participants for both identification and definition of a problem. The generation of possible solutions seemed to be marked by such words as ‘think’ and ‘maybe’ (together with its synonyms ‘possible’, ‘could be’ and ‘can’). The evaluation of possible solutions featured such elements as ‘better’ and ‘is correct’ or ‘is not correct’. In reference to external support (see Additional Phase of External Support in Table 1), we identified a number of words making reference to the use of external reference sources, both in general and in the particular.

2.7.2. Validation of action indicators

We decided to validate our working hypotheses for each action indicator, which required a complete analysis of all the occurrences of each given indicator in the corpus of conversations. We were aware of the fact that not all processes are open to labeling as only problematic processes are normally being verbalized due to automatic processing of unproblematic elements.

Our first working hypothesis was about the word 'understand' which seemed to make reference to text comprehension. We identified at least four contexts where this word was present, all of them related to comprehension though associated with different elements as we can see from the corpus selection in Table 2.

| 1. I don't understand

anything 2. I don't understand this exercise 3. I don't understand the world "moreover" for paying the debt? what does it mean? 4. yes but I don't understand this paragraph "this harassment affect to women employees whose employer is a man." 5. But [does] anybody understand the paragraph? 6. Yes, I understand the paragraph. 7. but I don't understand what it said 8. I don't understand this... I don't know 9. I don't know, I don't understand it 10. I don't understand the sentence... 11. I don't understand the sentence with the mistake 12. I think that the first mistake is "to claim" but I cannot understand it very well 13. I don't understand the mistake 14. but "their", we can't change... - I don't understand - the mistake is like, their is good 15. I don't understand you. Please, tell me the solution for: "For example, there is not equality between women’s and men’s salary. Do you agree 'enequality'? 16. I don't understand you |

Table 2: Selection from corpus used to validate ‘understand’ as a comprehension process indicator

We observed from this corpus selection that the word 'understand' makes reference to:

- the task in general (1, 2),

- a text or its element (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11),

- the error (12, 13, 14),

- a classmate’s suggestion for correction (15, 16).

All the indicators taken as working hypotheses were analyzed in a similar way (for details see Kozlova 2005: 307-316). The results of this validation are presented in Table 3. As we can observe from the first part of the Table referring to C and P processes, ‘solution’ was eventually not accepted as an indicator for production, ‘put’ was accepted without any restriction and ‘change’ was accepted with restrictions.

| PROCESSES |

ACTION INDICATORS |

| Comprehension

(C) |

understand (when a

reference is made to the source text or its element) |

| mean (in any form, such as

means, meaning, etc.) |

|

| Production

(P) |

put |

| change (when a target text

element is present) |

|

| PHASES OF INTERNAL SUPPORT |

|

| Identification

of a problem (I) |

problem (when features are

absent) |

| don’t know (when features

are absent) |

|

| Definition

of a problem (D) |

problem (when features are

present) |

| don’t know (when features

are present) |

|

| Generation

of possible solutions (G) |

think (except for when it

is a question) |

| maybe (except for when it

is an answer) |

|

| possible (except for when

it is an answer) |

|

| could be (except for when

it is an answer) |

|

| can (except for when it is

a request) |

|

| Evaluation

of possible solutions (E) |

better |

| is correct |

|

| is not correct |

|

| ADDITIONAL PHASE OF EXTERNAL SUPPORT |

|

| Resources

use (R) |

dictionary |

| Google |

|

| Altavista |

|

| translator |

|

Table 3: Indicators of processes and problem-solving stages after their validation in the entire corpus

In reference to internal support, both problem-identification and problem-definition phases seemed to be marked by the same elements: ‘problem’ and ‘don’t know’. We found that the difference between the two lies in the presence or absence of particular features of the problem. If these are present, like in the example “I don´t know, “in” or “on”, these words are treated as D-indicators, if not, then they are I-indicators.

As for generation of possible solutions, we had to exclude some specific cases: for instance, when ‘think’ was part of a general inquiry “What do you think?” or when ‘possible’ and ‘could be’ were used to support somebody’s suggestion.

All the 13 occurrences of the word ‘dictionary’ in the corpus appeared to be related to the intention of the participants to look up a certain element. The same happened to other, less frequent, indicators.

3. Data Analysis and Results

The data about the acceptability of results, making reference to the product, was collected after evaluating each group’s corrections. Given that each group had to correct 10 mistakes in the assigned text, the maximum acceptability is 10 out of 10. The aforementioned product analysis was later contrasted with the process analysis.

3.1. Hypothesis 1

To prove this hypothesis, we analyzed the sequences leading to acceptable solutions (A-sequences). First, with both C- and P-indicators present, then only with P-indicators and, finally, only with C. The sequences, coded according to the group and the problem number, are presented in their reduced form in Table 4.

| Code1 |

Sequence2 |

Result |

| T7 |

CCPPP |

A |

| A3 |

CCCCCCCCCCCPP |

A |

| T9 |

PCPPP |

A |

| A9 |

PCP3 |

A |

| V2 |

P |

A |

| V3 |

P |

A |

| W2 |

PPP |

A |

| W3 |

P |

A |

| W5 |

PP |

A |

| T4 |

P |

A |

| P5 |

P |

A |

| A8 |

P |

A |

| A10 |

P |

A |

| P9 |

P |

A |

| A5 |

P |

A |

| M7 |

P |

A |

Table 4: Problem-solving sequences which led to acceptable results

As only the first 2 out of 16 A-sequences (T7 and A3) followed our hypothesized order - production follows comprehension in text reproduction - we have discovered that there were more cases to consider. Namely, the sequences T9 and A9 started with production, then went to comprehension and later returned to production. We could question if this order is efficient as at the end of the day the participants had to follow our hypothesized C->P order. We found a lot of acceptable sequences where only the P-indicator was present. In contrast, there appeared to be no A-sequence at all where only the C- indicator was present.

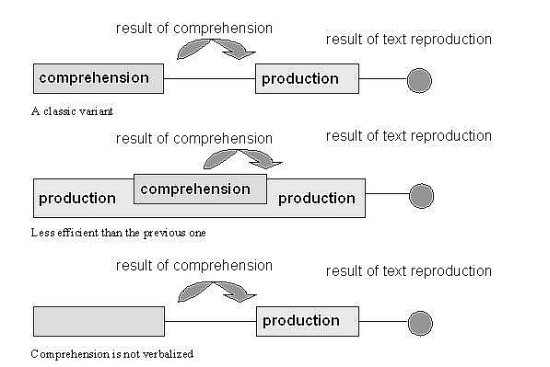

We could interpret these results by suggesting that comprehension is the part of text reproduction that is taken for granted by students and is often performed automatically when it presents no problem, which is why it is not verbalized. In contrast, production is perceived as an explicit and final task, so it is always present. In Figure 1 we provide a summary of possibilities for comprehension and production sequencing in text reproduction.

Figure 1: Three variants of comprehension and production sequencing as found in problem-solving with acceptable results

3.2. Hypothesis 2

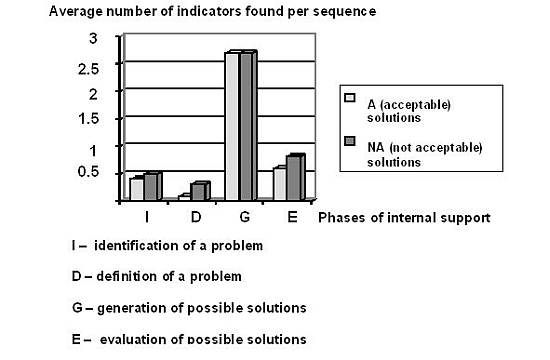

The next hypothesis was aimed at discovering the relationship between the number of indicators of internal support (I, D, G and E-indicators) and the acceptability of results. We hoped to prove that a more in-depth cognitive implication leads to better results. For this purpose, we analyzed all the problem–solving sequences where any of the aforementioned indicators appeared. Then, we calculated average density for each indicator in each sequence, with both acceptable and unacceptable results. To provide an illustration, we found 92 instances of G-indicator in the total of 33 A-sequences and 72 instances of G-indicator in the total of 27 NA (Not Acceptable)-sequences which gives us G-indicator density of 2.7 for both A- and NA-sequences as presented in Graph 1.

Graph 1: Internal support indicators’ density in A (acceptable) and in NA (not acceptable) solutions

We can observe that, contrary to what we hypothesized, the density of internal support indicators was generally higher in sequences that lead to NA results, which was the case of I, D and E-indicators. This means that the students’ cognitive effort was greater in sequences with NA solutions but nonetheless they failed. As for the density of G-indicator, we found that it was the same in A as in NA sequences, which may indicate that the effort at this stage is not related to the results. This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that students dedicate the same cognitive effort to each sequence and, when at a loss, dedicate more effort to identifying and defining the problem, and normally then there is more controversy within the group concerning the final decision.

3.3. Hypothesis 3

To prove that a more in-depth query of external reference sources leads to better results we analyzed all the R-present sequences (listed in Table 5).

|

Code |

Sequence |

Result |

|

V2 |

GIGRIRGPE |

A |

|

P3 |

(D)IRRRR |

A |

|

A1 |

(G)DGGRRGGI |

A |

|

A3 |

CRCCC(R)CIGGECCIRCRGGCCEGCRGEGEGEIPGP(R)ERGEGE |

A |

|

A6 |

GG(D)(R)GEGGEGE |

A |

|

A7 |

G(R)G |

A |

|

A9 |

(G)E(G)RRRGGGPIGEIGGEG(C)P |

A |

|

W7 |

GPRPGCGDCGGECIPGGPGEGPCGPCCEPEGGEPGPPPGGP |

NA |

|

T5 |

(G)ICCRGEICECIICCCCGI |

NA |

Table 5: The R-present sequences and their outcomes

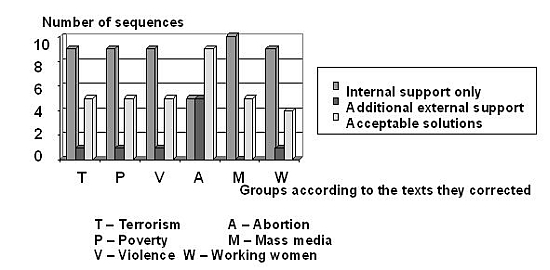

The result of our analysis is shown in Graph 2. While the majority of groups used mostly internal support, group A (the group that worked on the text titled Abortion) combined both internal and external support. As a result, while the majority of groups had an average of 5 acceptable solutions out of 10, in group A this number increased to 9.

Graph 2: External support as related to acceptability of results

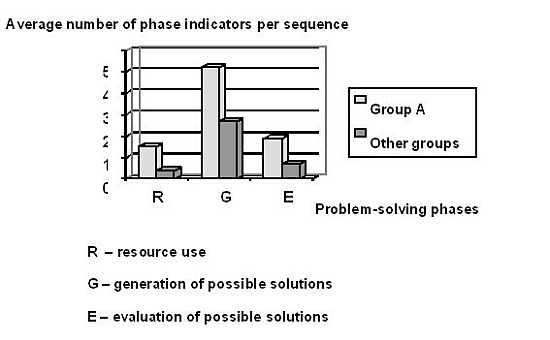

These results posed the question of why group A was able to achieve such an extraordinary result, as compared to other groups. To answer this question, we analyzed the sequences of group A as contrasted to the total of the other groups’ sequences. The results appear in Graph 3. We can observe that not only are there more R-indicators per sequence in group A, but also there are more G- and E-indicators, which means internal support in group A was more intense than in the rest of the groups as demonstrated in Graph 3.

Graph 3: Internal support as related to the acceptability of results (group A is contrasted to other groups)

This conclusion takes on particular importance when considered in the context of our Hypothesis 2. Previously, we failed to prove there is a relation between more intense internal support and better results. Now, our findings indicate that more intense internal support does help better results, though only when combined with external support.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

4.1 Study design

The design of our study proved itself to be effective and the method of labeling results very useful. However, we should mention some drawbacks to this method. First, it is necessary to remember that this method only allows problematic processes to be recorded while automatic processing relying on competences is not verbalized and is left out of focus. Second, each problem-solving phase allows for innumerable realizations and we had only the most common indicators of problem phases, which were characteristic of our participants. On the other hand, sometimes no specific word marked the phase but it was presupposed, like in dictionary quotation in A6. We recognize that our system of labeling in its present form could be improved.

In reference to the task design, we should be aware of the fact that students’ interpretation of the task may not completely coincide with our idea of it as researchers. First, student perceived the task as a kind of game, given that communication took place in the same classroom via computer. The task would certainly gain in authenticity if chat conversations were carried out from different locations and asynchronously, which would also allow more time for students to consult external sources. At present, we observed that the students seemed to assign comparatively little value to resources and relied instead on their own knowledge and intuition, an attitude questioned in the present study. The students’ evaluation criteria were their personal satisfaction, which of course often did not coincide with the teacher’s decision on acceptability. We expected our students to consult resources more and use their knowledge to evaluate solutions obtained from dictionaries, thus getting closer to the teacher’s normative perspective. Most students failed to obtain the necessary external support, although they were aware of insufficiency of their own internal support: the students’ global satisfaction with their results (64%) almost coincided with the proportion of solutions qualified as acceptable by the teacher (66%), as the post-task questionnaire revealed.

4.2. Study conclusions

Our study discovered the following tendencies:

- In text reproduction, the comprehension process should be finished before the production process can be finished.

- A more in-depth query of external resources is directly related to better results.

- A more in-depth cognitive implication alone seems not to be related to better results. However, a more in-depth cognitive implication supported by external inquiry is related to better results.

Our first conclusion suggests that in text reproduction its second part, production, depends on the result of the first part, comprehension. The fact that students attempt production before comprehension may be explained by their tendency to minimize their efforts. However, starting production before comprehension is not efficient, as we saw in the sequences where production starts, later is abandoned and is taken up again after comprehension.

Our second conclusion confirms that external support is helpful to achieve better results in text reproduction in a foreign language. This idea is not new and practically taken for granted in text reproduction such as translation, so we just focused on proving it generally.

Our third conclusion, however, is somewhat surprising. It could be expected that a more in-depth cognitive implication is associated with better results. However, we discovered that this is not so, at least until external support intervenes. Our students, like many others, tend to rely on their existing language knowledge and recycle it while performing the task. However, communication strategies as part of internal support solve the problem only partially. Students, especially LSP students, need to change their attitude, not only because the teacher wants them to progress, but because this becomes their professional necessity. Michael Rundell (1999: 38) mentions the problem that recycling already existing knowledge reduces the incentive to learn new items and expand one’s vocabulary. However, both in language instruction and in real tasks, external resources are more important than this because they allow the individual to obtain information otherwise unavailable. Thus our third conclusion reveals the real extent of internal and external support. External support is viewed by us as supplementary to internal support. It helps to complete the information the user lacks at certain stages of the problem-solving process. Somewhere else (Kozlova, 2005) we describe how external support helps to supply information that is lacking during the phases of generating and evaluating possible solutions (pp. 250-252). The decision is always taken in the working memory, which, as Stevick (1996) put it, “refers to a capability for consciously handling data from both external and internal sources” (p.28).

Footnotes

1 The letter indicates the first letter of the text and the number refers to the number of the problem marked in the text and later solved by the students (i.e. the third mistake to correct in summary Terrorism is coded as T3).

2 Here we present each sequence in its simplified form: while it is GCCPGPGGE, we only show CCPP.

3 We should specify that in one case, the C-indicator was not present but was easily deducible from the conversation as students translated the entire sentence into Spanish in order to understand the meaning of the problematic element (sequence A9).

References

Chandler, J. (2003). The efficacy of various kinds of error feedback for improvement in the accuracy and fluency of L2 student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 12 (3), 267-296.

Ferris, D. R. (2002). Treatment of error in second language student writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kelm, O. R. (1992). The use of synchronous computer networks in second language instruction: A preliminary report. Foreign Language Annals, 25, 441-454.

Kozlova, Inna (2005). Competencia instrumental en la reproducción textual en lengua extranjera: Procesos de consulta léxica en fuentes externas. PhD Dissertation, Department of Translation and Interpreting. Available http://www.tesisenxarxa.net/TDX-1128106-112356/index.html [Accessed: December 11, 2006]

Rickheit, G. & Strohner, H. (1989). Textreproduktion. In G. Antos, & H. P. Krings (Eds.), Textproduction. Ein interdisciplinären Forschungsüberblick. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Robb, T.; Ross, S. & Shortreed, I. (1986). Salience of feedback on error and its effect on EFL writing quality. TESOL Quarterly, 20, 83–91.

Rundell, M. (1999). Dictionary Use in Production. International Journal of Lexicography, 12 (1), 35-53.

Sengupta, S. (2001). Exchanging ideas with peers in network-based classrooms: An aid or a pain? Language Learning and Technology, 5 (1), 103-134.

Sternberg, R. J. (1996). Cognitive Psychology. Forth Worth: Harcourt Brace.

Stevick, E. W. (1996). Memory, Meaning and Method. A View of Language Teaching. Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

Vician, Chelly, & Brown, Susan A. (2000). Unraveling the message quilt: A case-study examination of student interaction in computer-based communication assignments. Computers and Composition, 17, 211-229.

Yuan, Yi. (2003). The use of chat rooms in an ESL setting. Computers and Composition, 20, 194-206.

Dictionaries used in the task:

Collins English Dictionary. (5th edition). [Original edition: 1979] and Collins A-Z Thesaurus. (1995). Software “Lexibase” (c) Softissimo 2002 v.5.1 Harper Collins Publishers.

Collins Spanish Dictionary. (7th edition). (2003). Harper Collins Publishers. [Original edition: William Collins Sons Co Ltd (1971)]. Software “Lexibase” (c) Softissimo 2002 v.5.1

_____

Kozlova, I. (2007). Studying Problem Solving through Group Discussion in Chat Rooms. Scripta Manent, 3(1), 35-51.

© The Author 2007. Published by SDUTSJ. All rights reserved.

Scripta Manent 3(1)

» J. Krajka

Online Lexicological Tools in ESP – Towards an Approach to Strategy

Training

» A. Curado

Fuentes

Lexical Acquisition

in ESP via Corpus

Tools: Two Case Studies

» I. Kozlova

Studying Pproblem Solving through

Group Discussion

in Chat Rooms

» M. Šetinc

Militarwörterbuch

Slowenisch-Deutsch (Wehrrecht und Innerer Dienst) / Vojaški slovar,

Slovensko-Nemški (Vojaško pravo in Notranja služba) and

Militarwörterbuch

Slowenisch-Deutsch (Infanterie) / Vojaški slovar, Slovensko- Nemški

(Pehota)

A review

Other Volumes