Home | Call for Papers | Submissions | Journal Info | Links |

Journal of the Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

ISSN: 1854-

Rachel Lindner

Introducing a Micro-

ABSTRACT

This article is concerned with the design of an English for Specific Purposes (ESP)

course, “Exploring English for Sociology”, at a German university. It focuses on

that aspect of the course that involves the development of intercultural content

aimed at facilitating intercultural competence. The first part of the article puts

forward a rationale for introducing an intercultural dimension to the syllabus. In

the second part I develop a case for combining “skills-

Keywords: English for specific purposes, teaching English for intercultural communication, English for sociology.

1. Introduction

The last 20 years have seen profound changes in Higher Education (HE) study patterns

as an increasingly mobile student population seeks educational opportunities and

improved career prospects in study sojourns and internships abroad. In German HE

this development has brought with it a rise in demand for English language courses,

notably from students of non-

In ESP, where learning English is increasingly seen “as part of the wider process

of socialisation into a new academic community” (Corbett, 2003: 68), a response to

this demand has been to supplement the traditional focus of reading and writing for

academic purposes with communicative skills development. However, this response alone

is unlikely to meet the needs of internationally engaged students: Alptekin (2002)

argues that much communicative language teaching (CLT) is based on native-

A look at English teaching paradigms in Germany sheds more light on what appears to be a mismatch between ESP learner needs and language teaching practice.

1.1. A need to shift English teaching paradigms?

Figure 1 adapts Braj Kachru’s (1985, in Graddol, 2006) depiction of the global community

of English speakers to illustrate English language teaching in Germany, where learners

of English belong to the expanding circle of English speakers in which English is

learned as a foreign language (EFL). Of the inner circle varieties, British English

is traditionally used to provide an authoritative native-

Figure 1: Traditional TEFL paradigm in Germany. Adapted from Kachru’s (1985) circles of Englishes

The global spread of English and its subsequent lingua franca status has had little

impact on the German school curriculum. It is true that English has become a core

compulsory subject from age eight, modern textbooks portray a slightly more differentiated

British society and more space is dedicated to other inner circle Englishes. Even

so, the thrust of English learning remains firmly within the TEFL paradigm (see e.g.

Decke-

Unsurprisingly the TEFL paradigm is similarly dominant amongst many lecturers and

language teachers in higher education establishments, for whom the principle goal

of language learning remains native-

Teaching English as an International Language (TEIL), as a Lingua Franca (TELF) and

for Intercultural Communication (TEIC) have emerged in response to the global spread

of English and the subsequent changing needs of learners. In comparison to TEFL,

which is culture-

Literature on TEIL, TELF and TEIC often uses the terms interchangeably. In this article

TEIL and TELF are seen as providing more linguistically-

In contrast to TEFL the goal of TEIC is not so much native-

Figure 2: Newer teaching paradigms. Adapted from Kachru’s (1985) circles of Englishes

Referring back to emerging English learning needs of students of non-

2. Defining intercultural content

An often cited set of objectives for intercultural content is Byram’s five “savoir” categories or “components of intercultural competence” (Byram, 1997; Byram and Zarate, 1997; Byram et al, 2002), which form the basis of the CEFR guidelines for intercultural learning, teaching and assessment (Little and Simpson, 2003).

Figure 3: Byram’s five “savoir” categories (adapted from Byram, 1997)

With their emphasis on the development of skills, attitudes and understanding, the

five “savoir” categories provide a useful framework of objectives that encourages

the learner to take a step back from arbitrary cultural information and national

stereotypes and to develop instead a more critical insight into both their own and

other cultures – the learner is invited to become a critical participant-

Most importantly, by focussing on critical and analytical skills and attitudes, the

framework can be flexibly applied to a wide range of learning situations (Byram et

al, 2002: 17). It can be applied to the TEFL paradigm – a group of German Canadian

Studies students preparing for a sojourn at a Canadian university, for example. Thinking

further, it is equally relevant for lingua-

2.1. Focus on intercultural “micro-

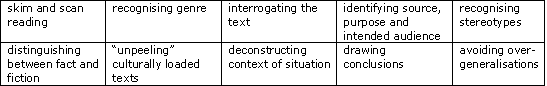

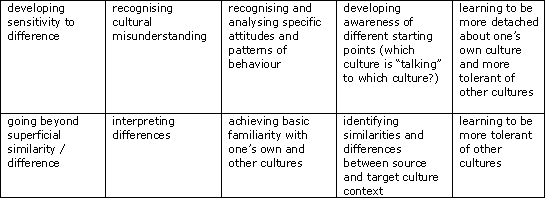

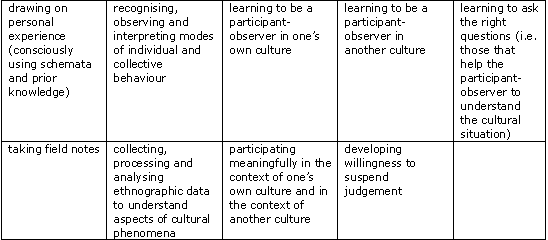

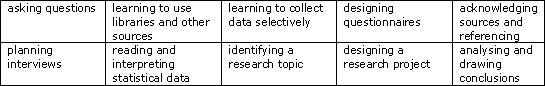

The Cultural Studies Syllabus (CSS) Branching Out (British Council, 1998) is an example

of a language syllabus in which skills for intercultural learning have been made

an integral component of syllabus design (cf. Figure 4). Developed in Bulgaria as

part of a language and culture project, the syllabus is organised around four sets

of analytical skills geared towards furthering cultural awareness (see also Figure

4 and British Council, ibid: 24-

-

-

-

-

1. Critical reading and listening skills

2. Comparing and contrasting skills

3. Ethnographic skills

4. Research skills

Figure 4: Cultural Studies Syllabus (adapted from British Council: 1998, 24-

In keeping with Byram’s views on intercultural learning expressed in the “savoir” framework, the CSS developers felt that language learning should be partly about developing skills that help students to analyse, understand and appreciate cultural diversity and sensitise them to different cultures (British Council, ibid: 12). The syllabus should “give primary place to developing in students the ability to use tools for understanding by means of questioning and analysing the information supplied in various forms, for example through the media, tourist literature, medical leaflets and literary texts.” (Davcheva et al, 1999: 64).

Although the CSS was originally intended for TEFL practitioners in Bulgarian schools,

its ideas and materials have extended beyond the target audience, thus exemplifying

the flexibility of the skills it sets out to teach. Indeed, it is highlighted here

as an example of “skills-

Language learning: Many of the micro-

Academic learning: There is a clear fit between the four-

Intercultural learning: The Sociology students participating in the ESP course may

not be planning to undertake a sojourn or do an internship abroad at present. However,

they do need to deal with a wide variety of print and, increasingly, online English-

2.2. Terminological clarification

Before discussing how intercultural content has been implemented in the ESP course for Sociology students, this seems a good point to take stock of the key terminology used so far in this article.

The term “intercultural” refers to comparing two or more cultures. I use “intercultural”

rather than “cultural” because the latter is often used in the literature with reference

to TEFL paradigms in which a target language is explicitly linked to a target culture

in the inner circle of English speakers. In section 1 it was argued that the learner

group needs English as much for NNS-

Drawing on the foregoing summary of terminology, it can be said that the principle objective of “Exploring English for Sociology” is to combine language learning with the development of skills such as those identified by the CSS in order to foster intercultural competence and intercultural awareness. These may in turn serve as the foundation of effective ICC.

3. Implementing the intercultural dimension

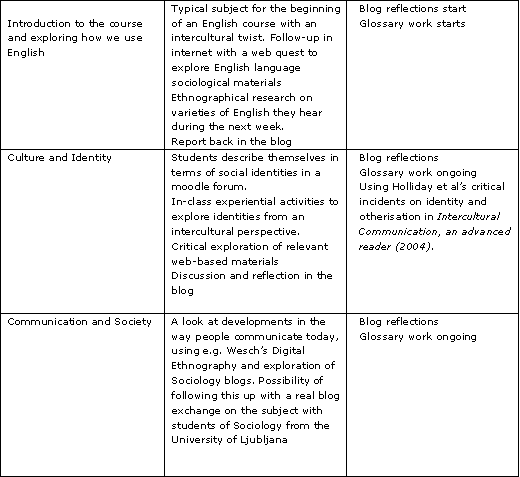

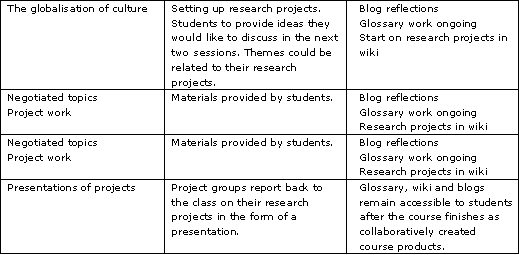

“Exploring English for Sociology” is open to Sociology students of any semester with a Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) language proficiency of B2 upwards.

Blended learning: The course comprises seven face-

Skills-

Part-

3.1. Features of task design

Tasks are designed to combine communicative and intercultural approaches to language learning. Corbett (ibid), Byram et al (2002), Alptekin (2002), Stifakis (2003) and Prodromou (1992) provide some useful pointers for task design, which are here summarised as follows:

Giving familiar themes and activities an intercultural twist: Many themes and activities

from ELT textbooks lend themselves to an intercultural approach. In the materials

developed for the first face-

Familiarisation with vocabulary that helps learners speak about intercultural diversity: In “Exploring English for Sociology” many terms from the intercultural field are also found in the sociological field, although sociology and ICC may have different understandings of these terms. The course therefore provides opportunities to explore this terminology in depth, for example in a collaboratively produced glossary of terminology.

Make sure learners understand the context and intention of materials: The micro-

Explorations of opinion gaps as well as information gaps: Byram et al (ibid: 25)

recommend opinion as well as information gap activities that promote the “sharing

of knowledge and a discussion of values and opinions” involving comparing and contrasting

skills. To support the kind of reflection required in activities of this kind, a

blog has been set up for the course, in which students are encouraged to exchange

opinions in writing between the face-

Learner attitudes: Sifakis (2003) and Prodromou (1992) both emphasise the importance

of finding out about learner attitudes in cross-

Instructional materials should include different varieties of English: Alptekin (2002:

63) notes the importance of a mixture of discourse samples from NNS-

4. Concluding thoughts

There are several factors that speak in favour of the success of the learning approach

outlined in this paper: “Exploring English for Sociology” attempts to balance the

development of familiar communicative skills and English for Academic Purposes objectives

with less familiar intercultural skills and to integrate this into topics and materials

of interest for sociologists; students are invited to shape the syllabus with their

own topic ideas and materials; above all, the micro-

If a key aim of this course is intercultural competence and intercultural awareness,

the desired long-

One final consideration is the transferability of the course concept. Karastateva

et al (2007) argue that greater advantage should be taken of ESP lessons for teaching

students of non-

References

Alptekin, C. (2002). Towards intercultural communicative competence in ELT. ELT Journal

56(1), 57-

British Council (1998). Branching Out: A Cultural Studies Syllabus. Sofia: Tilia.

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and Assessing Intercultural Communicative Competence. Cleveland: Multilingual Matters.

Byram, M. and Zarate, G. (1997). Defining and assessing intercultural competence:

Some principles and proposals for the European context. Language Teaching 29, 14-

Byram, M., Gribkova, B. and Starkey, H. (2002). Developing the intercultural dimension in language teaching. A practical introduction for teachers. Brussels: Council of Europe.

Corbett, J. (2003). An intercultural approach to language teaching. Cleveland: Multilingual Matters.

Davcheva, L., Reid-

Decke-

Ehrenreich, S. (2009). English as a lingua franca in multinational corporations – exploring a business community of practice. Forthcoming.

Graddol, D. (2006). English Next. Why global English may mean the end of “English as a Foreign Language”. Plymouth: British Council.

Holliday, A. (1999): Small Cultures. Applied Linguistics, 20(2), 237-

Karastateva, V., Tsoneva, N. and Balciunaitiene A. (2007). Cultural Studies in LSP

Syllabus at Tertiary Level. Studies About Languages, 10, 60-

Kramsch, C. (1995). The cultural component of language teaching. Language, Culture

and Curriculum, 8(2), 83-

Little, D. and Simpson, B. (2003). English Language Portfolio: The intercultural component and learning how to learn. Council of Europe. Available:

http://www.coe.int/T/DG4/Portfolio/documents/Templates.pdf (4 December 2009).

Prodromou, L. (1992). What culture? Which culture? Cross-

Sifakis, N. (2004). Teaching EIL-

Wandel, R. (2002). Teaching India in the EFL classroom: A cultural or an intercultural

approach? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 15(3), 264-

Appendices

Appendix 1: Overview of the syllabus

Session Information

Appendix 2: Getting to know each other in sociological terms

-

-

Find someone who …

1. Comes from a different European country.

2. Comes from a different non-

3. Can speak three or more languages fluently.

4. Has lived in Munich all their lives.

5. Has more than four siblings (brothers and sisters).

6. Comes from a multicultural family.

7. Worked full-

8. Is older than 24.

9. Is younger than 21.

10. Comes from a different area of Germany (i.e. not Bavaria).

Appendix 3: Critical reading – interrogating texts

When we’re reading texts or watching/listening to audio-

We can ask critical questions to help us, such as the following:

1. What are the materials about?

2. Where and when were the materials produced?

3. Who is the author, what is his area of specialisation?

4. Who is speaking/presenting (in videos, for example)

5. What kind of publication/video is it (e.g. commercial or institutional)?

6. Who is the intended audience?

7. What kind of English is being spoken/written? e.g. native speaker or a non-

8. What is the intention of the materials (persuade, argue, entertain, to sell something)?

9. Do the materials interest you, entertain you, educate you, make you feel angry ... and why?

Ideally, you should then compare your answers, feelings and opinions with other members of the group.

Try out the interrogating technique now in the following activity:

-

-

-

Appendix 4: Questionnaire: English experience and English needs

-

-

-

1. How many years have you learned English?

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

2. When did you last do an English course?

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

3. Which variety of English did you come into contact with at school?

(a) British English

(b) American English

(c) Other (please specify)

(d) A mix

(e) Don’t know

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

4. Do you intend to study abroad during your studies or do an internship in a country where you will probably need English?

(a) Yes

(b) No

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

5. Indicate on a scale of 1 to 5 the probability that you will need English in your future careers (one is the lowest probability, 5 is the highest probability).

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

6. What is it important to practise/learn in this course? You can choose as many points as you like and add others.

(a) Discussion of Sociology topics in English

(b) Skills for intercultural communication with other English speakers

(c) A critical understanding of text-

(d) A critical understanding of reading and listening materials written for and by sociologists who are native speakers of English

(e) Other (please specify)

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

7. Is the English you come into contact with now or think you will come into contact with later in your studies...

(a) native speaker English

(b) non-

(c) both

(d) don’t know

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

8. For what purpose do you need English now or think you will need it for later?

(a) For reading books and articles on your reading list

(b) For understanding audio-

(c) For research on the internet

(d) For writing assignments/papers

(e) For communicating with people about Sociology online

(f) For communicating with people about Sociology face-

in lectures, with visiting students, at conferences etc.)

(g) Other (please specify)

Your answer:

Your partner’s answer:

© 2005-

Scripta Manent Vol. 5(1-

» Contents

What Degree of Specificity for ESP Courses in EFL Contexts?

» R. Lindner

Introducing a Micro-

Previous Volumes