Journal of the

Slovene Association of LSP Teachers

Journal of the

Slovene Association of LSP TeachersISSN: 1854-2042 |

|

Home | Call

for Papers | Submissions | Journal Info | Links | |

Sara Laviosa

Wordplay in Advertising: Form, Meaning and Function

ABSTRACT

Generally speaking, wordplay (or pun) is a witticism that relies for its effect on playing with different levels of language, i.e. phonological, graphological, morphological, lexical, syntactic, and textual. Puns are frequently used in commercial advertising as a rhetorical device to promote a given product or service by creating humour, attracting the reader’s attention and adding persuasive force to the message. They also reflect the cultural preferences and traditions of a country, therefore they can be fruitfully used for pedagogic purposes to raise awareness of the specific linguistic and cultural features of the foreign language. In this paper I examine the form, meaning and function of puns that rely on the different meanings of polysemic words, the literal and non-literal senses of idioms or on bringing two homonyms together in the same utterance to produce witty remarks. After introducing the notions of homonymy, polysemy and idiom I analyse the play on words contained in a sample of advertisements selected at random from two broadsheet newspapers, The Guardian Weekend (1997) and The Independent (1997), two quality weekly magazines, Cosmopolitan (1997) and The Telegraph Magazine (1997), as well as a promotional brochure by Alliance & Leicester plc (2003) and promotional leaflets published in 2000 respectively by Royal Mail, British Telecommunications plc and Johnson & Johnson. Finally, I propose some activities that can be carried out in the LSP classroom either individually or in groups to raise awareness of some of the linguistic and cultural features characterizing the rhetoric of marketing and promotion in business language.

© 2005 Scripta Manent. Slovensko društvo učiteljev tujega strokovnega jezika.

Generally speaking, wordplay (or pun) is a witticism that relies for its effect on playing with different levels of language, i.e. phonological, graphological, morphological, lexical, syntactic, and textual. Puns are frequently used in commercial advertising as a rhetorical device to promote a given product or service by creating humour, attracting the reader’s attention and adding persuasive force to the message. They also reflect the cultural preferences and traditions of a country, therefore they can be fruitfully used for pedagogic purposes to raise awareness of the specific linguistic and cultural features of the foreign language. In this paper I examine the form, meaning and function of puns that rely on the different meanings of polysemic words, the literal and non-literal senses of idioms or on bringing two homonyms together in the same utterance to produce witty remarks. After introducing the notions of homonymy, polysemy and idiom I analyse the play on words contained in a sample of advertisements selected at random from two broadsheet newspapers, The Guardian Weekend (1997) and The Independent (1997), two quality weekly magazines, Cosmopolitan (1997) and The Telegraph Magazine (1997), as well as a promotional brochure by Alliance & Leicester plc (2003) and promotional leaflets published in 2000 respectively by Royal Mail, British Telecommunications plc and Johnson & Johnson. Finally, I propose some activities that can be carried out in the LSP classroom either individually or in groups to raise awareness of some of the linguistic and cultural features characterizing the rhetoric of marketing and promotion in business language.

© 2005 Scripta Manent. Slovensko društvo učiteljev tujega strokovnega jezika.

Introduction

In the vocabulary of any language words are linked together into a sort of gigantic spider’s web organized by principles that are language specific. Sense relations constitute one of these organizing principles, they refer to how words relate to each other in terms of their meaning, that is how similar or different or general or specific they are to one another. Homonymy and polysemy are two types of sense relations. Homonymy is the sense relation that links homonyms, that is words that have the same sound and spelling but different meanings. For example the three meanings listed in Table 1 below are expressed by the same word-form bank, which therefore has three homonyms.

| MEANING | a financial institution that people or businesses can keep their money in or borrow money from | a raised area of land along the side of a river | a large number of pieces in a row, especially pieces of equipment |

| EXAMPLE | the Royal Bank of Scotland | the east bank of the river Severn | a bank of TV monitors |

Table 1. Meanings of the word-form bank1

Polysemy is the term used to refer to the different meanings conveyed by the same word. Words that have more than one propositional meaning are called polysemous (or polysemic) words as opposed to monosemous (or monosemic) words, which convey only one propositional meaning. An example of polysemy is given by the noun model, whose different meanings are listed in Table 2.

| M E A N I N G |

a small copy of something such as a building, vehicle, or machine | something that is so good that people should copy it | someone or something that is a good example of a particular quality | someone whose job is to show clothes, make-up, hairstyles, etc. | someone

whose job is to be drawn or painted or photo- graphed by an artist |

a particular type of vehicle or machine that a company makes | a simple technical description of how something works |

| E X A M P L E |

a model of the Eiffel Tower | many countries have shown an interest in the Chinese farming model | the school was a model of excellence | Eileen wants to be a fashion model | a

nude model |

Fiat launched a new model last year | chapter 5 presents an alternative model for the country’s economic structure |

Table 2. Meanings of the noun model

An idiom is a multi-word unit whose meaning cannot be generally inferred from the meaning of the individual words. Idioms vary from being semantically opaque such as to break the ice meaning “to say or do something to make people feel relaxed and comfortable”, to being semi-opaque such as to pass the buck meaning “to pass the responsibility”, or being relatively transparent such as to see the light meaning “to understand”. Idioms that are difficult to recognize are those that have a literal as well as an idiomatic meaning, such as to go out with somebody, to take someone for a ride, to put one’s feet up, to pull somebody’s legs, to have cold feet, or to put something on ice.

Wordplay (or pun) is a rhetorical device that often relies on the different meanings of a polysemic word, the literal and non-literal meaning of an idiom or on bringing two homonyms together in the same utterance to produce a witticism. Punning is frequently used in commercial advertising to attract the reader’s attention and maintaining her/his interest in keeping with the AIDA principle (Lund, 1947: 83), whereby the language of advertising must attract the Attention of the prospective buyer, maintain her/his Interest, create a Desire, and get her/him into Action. By playing with the similarity of form and the difference in meaning of given lexical items, the advertiser entices the reader to grasp the double meaning conveyed by the message, as if it were a sort of puzzle, as a result, Tanaka observes, “the effort made by an audience in recovering the intended effects of the advertisement is actually increased by punning” (Tanaka, 1994: 64). Moreover, the reader is gratified for having understood the witticism, this contributing to fulfilling the text’s conative function. Delabastita defines wordplay as a textual phenomenon, a fact of language which is inextricably linked to the structural features of language (Delabastita, 1996: 129), puns are also intimately bound up with the culture of a language, reflecting particular values, tastes and lifestyles. Furthermore, because of their humorous effect, puns are ideally suited to render commercial advertising witty, effective and memorable, as required by most big companies worldwide and recommended by Simon Anholt, managing director of World Writers in an article appeared in The Times (18th June 1997), where he states that “the winning ads are almost always funny” and “if you want to make friends and influence people, you need to start by raising a smile”. In the following section I analyse a sample of commercial advertisements focusing on the interrelationship between form, meaning and function of puns together with the role played by the cultural context to disambiguate their meaning. The methodological approach adopted is primarily linguistic. The aim is to illustrate how the linguistic analysis of a sample of specialised language use can be useful in teaching the lexico-grammar of a foreign language as well as some subtle nuances of cultural meaning.

Playing with homonymy, polysemy, and idioms

The following advert by MG Rover Cars promoting its Land Rover is an example of wordplay which exploits the homonymy between spring meaning “a long thin piece of metal in the shape of a coil” and spring as “the season of the year between winter and summer”, which is particularly pleasant in England. In turn spring is portrayed as a man or woman receiving advice on “how to be beautiful”, thus providing a good example of what Haug (1971: 15) calls Warenasthetic, that is the aestheticization of commodities, whereby advertising makes products appear as pleasing and appealing as possible. The message in small print consists in fact of a list of instructions corresponding to the different stages of what appears to be a kind of beauty treatment. The association between the various phases of manufacturing a metal spring and the routine activities aimed at acquiring an ideal figure is obtained through the metaphorical use of the verbal phrases “feed yourself”, “take a dip” and “stretch […] your entire body”.

How to be

beautiful. First, feed yourself through a furnace.

ANOTHER

Then take a dip in hot oil. (About 10000C should be OK.)

BEAUTIFUL

After that, get blasted by small metal balls. Finally, stretch

ENGLISH

and compress your entire body to the limit 250,000 times.

SPRING.

Then, and only then, can you be fitted to the most stunning 4x4.

ANOTHER

Then take a dip in hot oil. (About 10000C should be OK.)

BEAUTIFUL

After that, get blasted by small metal balls. Finally, stretch

ENGLISH

and compress your entire body to the limit 250,000 times.

SPRING.

Then, and only then, can you be fitted to the most stunning 4x4.

© The Telegraph Magazine 1997

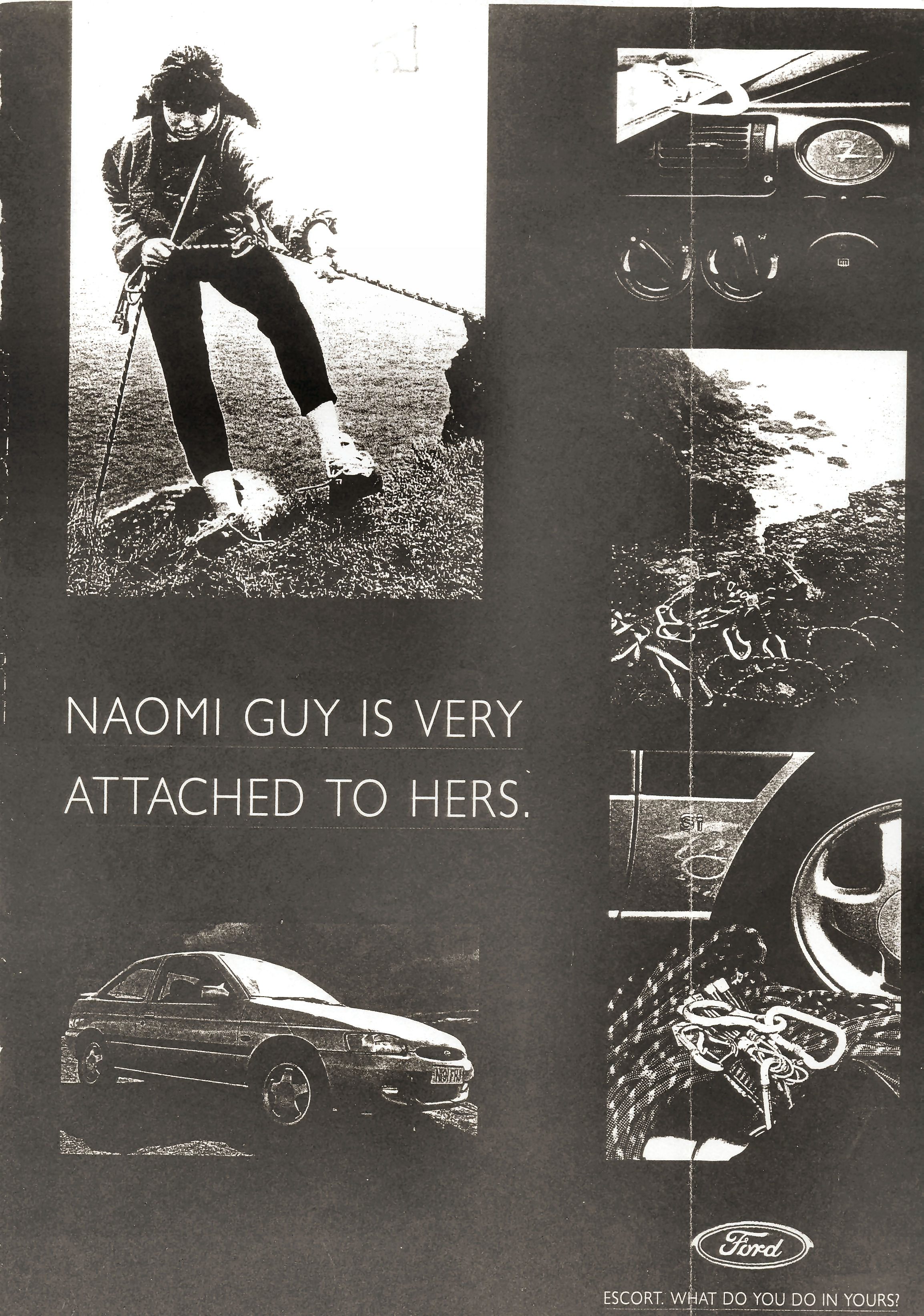

The following car advert by Ford Motor Company is an example of wordplay that exploits the polysemy of the adjective attached, which means either “joined or fixed to something” or “liking someone very much or loving them”. The picture shows a famous rock climber, Naomi Guy, who is climbing a very high cliff and is sustained by a rope that is firmly attached to her Ford Escort parked on top of the cliff. The slogan says: NAOMI GUY IS VERY ATTACHED TO HERS while

the slogan below the company logo reads: ESCORT. WHAT DO YOU DO IN YOURS?

© Cosmopolitan 1997

An example of a composite wordplay that exploits cultural differences enshrined in particular words and concepts is offered by the following ad, promoting the Cross & Blackwell Hollondaise sauce:

Botticelli

worked in oils, but all I needed was a knob of butter… And some milk.

Was this food? No, it was art. Silky smooth Hollandaise sauce ready in

5 minutes with the help of BONNE CUISINE. Should I eat it? Or send it

to the Tate Gallery?

©

Cosmopolitan 1997

In this ad there is a double pun, one arising from bringing two homonyms together: oil as “a thick smooth liquid used in cooking and preparing food” and oil as “a type of paint made from oil”, usually used in the plural, the other relating to the polysemy of the verb work which means either “to spend time trying to achieve something” or “to produce a picture or create an object using a particular type of substance”. So, through punning, the preparation of ready-made English meals, which often rely on local, economical products such as milk and butter, is at one time humorously contrasted with the laborious and expensive Italian cuisine, which makes a large use of olive oil, and equated to the art of painting, represented by the famous fifteenth century Florentine painter. In this advertisement typical cultural stereotypes associated with Italian art and cuisine are effectively exploited to capture and hold the reader’s attention and maintain her/his interest by appealing to national pride, habits and tastes.

Another illustration of wordplay that exploits in the same word the sense relations of homonymy and polysemy is provided by the advertisement below, which combines visual and verbal devices to raise a smile on the prospective client:

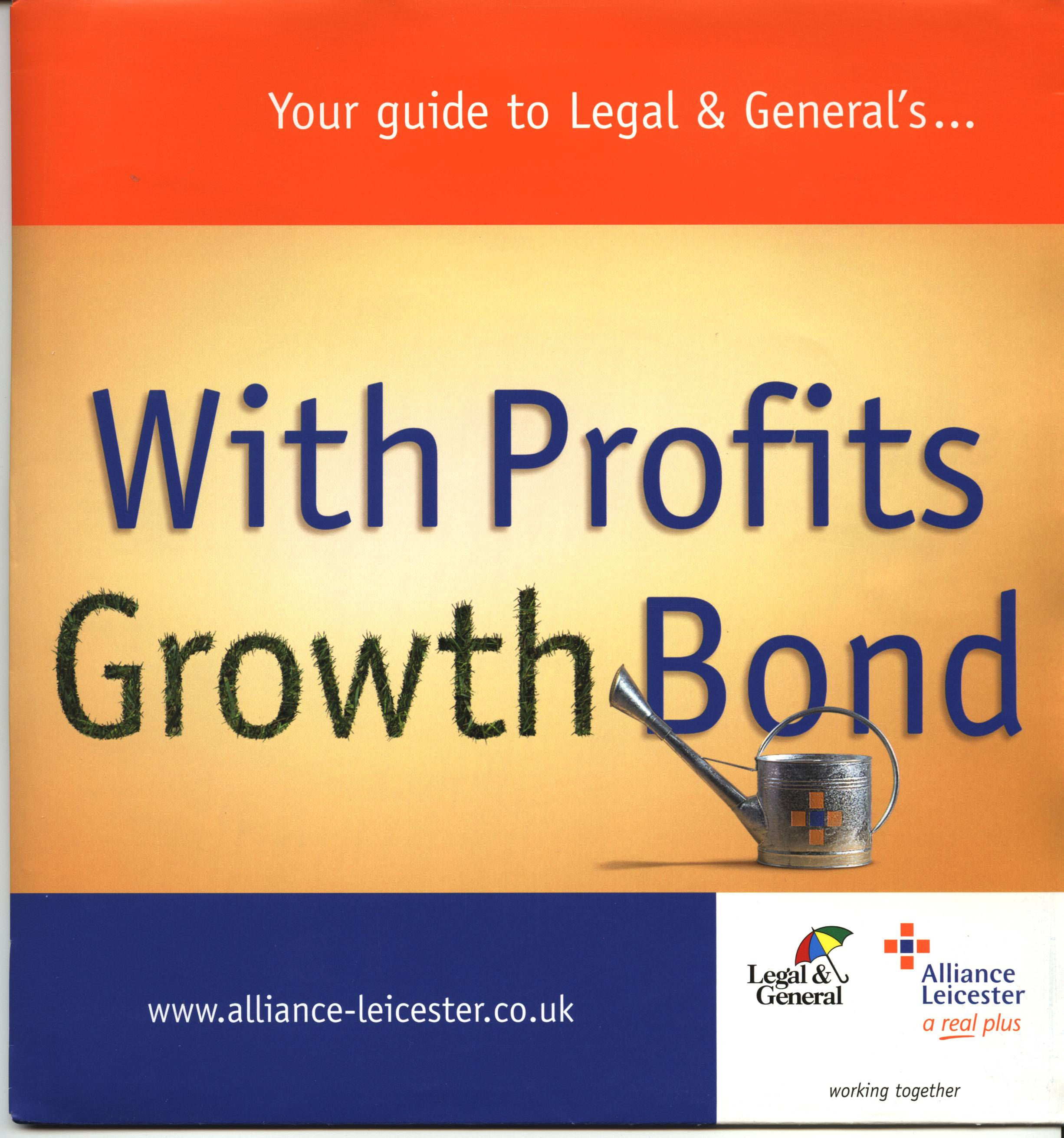

© Alliance & Leicester plc 2003

The ad appears on the cover pocket of a brochure promoting a new bond called “With Profits Growth Bond”, offered by the life assurance company Alliance & Leicester plc. The play on words is obtained visually by depicting the word “Growth” as if each letter had been cut out from a patch of lawn with fresh green grass growing on it, which is regularly watered, as indicated by the image of a water can placed next to the catchword. This is an example of visual pun, which consists in illustrating the two or more senses brought together by a verbal pun (Cook, 2001: 61). So, being part of the full name of the bond, “Growth” is a homonym of growth meaning “an increase in the amount of money invested in a business”. The additional meaning that “Growth” visually conveys in the ad is also “an increase in the size or development of living things, such as a plants and trees”. By associating the name of the bond with both economic growth and a carefully tended lawn, the pride and joy of most English people, the advertiser aims to convey, through familiar imagery, the idea of success, wealth together with a sense of security and well being with a view to gaining the reader’s trust and rendering the product desirable.

Idioms that have both a literal and an idiomatic meaning are often used creatively in wordplay as in the example below:

Thorntons

new

chocolates bars. Not everyone’s a fruit and nut case. Thorntons bring

you a new selection of chunky chocolate bars. Milk chocolate. Dark

chocolate. Autumn Nuts. Toffee. Winter Nut and Fruit. And Ginger.

You're spoilt for choice. So spoil yourself.

© The Guardian Weekend 1997

© The Guardian Weekend 1997

The ad promotes a new selection of chocolate bars produced by Thorntons, the famous British chocolate company since 1911. The witticism is created by playing with the idiom “to be a nut case” which means “to be mad or to behave in a strange way”. Thorntons, the advertiser intends to say, is not at all made but wise, because it does not limit its range of products to fruit and nut chocolate bars, like its competitor Cadbury, but it offers a delicious variety of fillings. The play on words - based on the literal and idiomatic meaning of the word nut as well as the addition of fruit and to form the coordinated noun phrase fruit and nut - which evokes Cadbury’s “fruit and nut chocolate bars” - has the effect of making Thorntons stand out to the detriment of its business rival, thus conveying what in advertising is known as the Unique Selling Proposition (Goddard, 2002: 4). This is a clear example where knowing about the specific cultural context that gives rise to an ad is often essential to disambiguate the subtle intended meanings conveyed by the creative use of promotional language.

Sometimes we find more than one witticism in the same ad, as in the following example provided by the Isuzu car manufacturing company promoting its Trooper 4x4:

Real

Troopers are never up the creek without a paddle.

© The Guardian Weekend 1997

© The Guardian Weekend 1997

The slogan is placed on top of an image portraying a barren landscape with a man fishing in a small river next to his Isuzu Trooper 4x4 in the foreground. The idiom “to be up the creek (without a paddle)” means “to be in a bad or difficult situation” and trooper means “soldier”. The double witticism is created by playing with both the literal and idiomatic meaning of the expression “to be up the creek”, which literally means “to go up a small stream or river”, and by bringing two homonyms together: the name of the advertised Isuzu car and trooper. In this instance the advertiser uses a clear ego-targeting strategy (Williamson, 1983) by fulfilling the reader’s need and desire to have a car that is able to take her/him wherever s/he wishes safely and comfortably, no matter how difficult or treacherous it may be.

Activities for the LSP classroom and Key

In my envisaged teaching sessions on wordplay in promotional business language within the context of English for business purposes, I would first of all introduce and illustrate the linguistic concepts that are necessary for understanding how puns work. I would then give students a series of activities to gain some practice in recognizing the linguistic features of verbal puns and reflect, wherever appropriate, on the cultural specificity of wordplay. The answers provided at the end of the activities concern only the linguistic features of wordplay, since they can be examined with a reasonable degree of accuracy and objectivity. No commentary is provided for the culture-bound aspects of the examples of advertising selected for practical classroom activities, since this type of analysis is better dealt with in group discussions where opinions can be shared and confronted.

First set of exercises: Analysis of sense relations

Identify the sense relations which have been exploited in the following examples of wordplay in commercial advertising. Wherever appropriate, comment on and discuss the cultural aspects that characterize these verbal puns.

a)

Moving

home? Let

us lighten the load. We can redirect your mail for up to two years.

That's one thing sorted ...

From a promotional leaflet © Royal Mail 2000

From a promotional leaflet © Royal Mail 2000

b)

“MUM’S TAKING US TO

LEGOLAND®

SHE'S AN ABSOLUTE BRICK.”

© The Independent 1997

SHE'S AN ABSOLUTE BRICK.”

© The Independent 1997

c)

“BOOK NOW FOR LEGOLAND®

DON’T WORRY, THEY TAKE PLASTIC.”

DON’T WORRY, THEY TAKE PLASTIC.”

©

The Independent 1997

d)

Net

a Million

You could win £1 million with BT Internet

From the 31st March until the 1 May 2000, BT Internet is offering you the chance to take part in the most exciting online promotion yet. All you have to do is get online and answer one question correctly and we will automatically enter you into the online free prize draw to win £1 million.

From a promotional leaflet © British Telecommunications plc 2000

You could win £1 million with BT Internet

From the 31st March until the 1 May 2000, BT Internet is offering you the chance to take part in the most exciting online promotion yet. All you have to do is get online and answer one question correctly and we will automatically enter you into the online free prize draw to win £1 million.

From a promotional leaflet © British Telecommunications plc 2000

e)

Your eyes will fall in love with

new 1-Day ACUVUE contact lenses. Arrange a date today. 1-Day ACUVUE.

Johnson & Johnson.

From a promotional leaflet © Johnson & Johnson 2000

From a promotional leaflet © Johnson & Johnson 2000

Key to the first set of exercises

a) polysemy: sort means either “to arrange things in groups or in a particular order” or “to solve a problem”;

b) homonymy between brick: “a small block of plastic or wood, used by children for building things” and the informal, old-fashioned word brick: “a nice helpful person”;

c) homonymy between plastic: “a very common light, strong substance produced by chemical process and used for making many different things” and the informal word plastic: “credit card”;

d) homonymy between the verb net: “to earn a particular amount of money after taxes or other costs have been removed” and the noun net: informal abbreviation of Internet;

e) polysemy: date means either “the name and number of a particular day or year” or “an arrangement to meet someone you are having or starting a sexual or romantic relationship with”.

Second set of exercises: Analysis of literal and idiomatic meanings

Identify the literal and idiomatic meanings which have been exploited in the following examples of wordplay in commercial advertising. Wherever appropriate, comment on and discuss the cultural aspects that characterize these verbal puns.

a)

Trust

our blend of

herbs and spices to get you out of a stew. Are your dishes tired, run

down, depressed? Take heart. The chefs at Knorr have just the remedy.

Eight different stock cubes created with one thing in mind. To enliven

everyday meals, so helping you ring the changes. It's all down to herbs

and spices. Which herbs and spices? That must remain a secret. As must

the blend. Their effect on appetite, though, is common knowledge.

© Cosmopolitan 1997

© Cosmopolitan 1997

b)

TIME

TO PUT THE

BOOT IN? The Peugeot 306 Sedan has 463 litres of boot space. Ours is

bigger. The Ford Scorpio has 465 litres of boot space. Ours is bigger.

The Mercedes E-280 Classic has 500 litres of boot space. And guess

what? Ours is bigger than that too.

NEW RENAULT Mégane Classic IT talks YOUR LANGUAGE

© Cosmopolitan 1997

NEW RENAULT Mégane Classic IT talks YOUR LANGUAGE

© Cosmopolitan 1997

Key to the second set of exercises

a) “to get you out of the stew” is a creative use of the idiom to be in a stew which means “to be very worried”; stew literally means “a meal made by cooking meat and vegetables in liquid at a low temperature”. The play on words is based on the double meaning of “to get you out of the stew” to convey the following message: with Knorr stock cubes we will take out your worries by enabling you to cook new tasty meals, rather than the old boring stew;

b) the witticism is based on the double meaning of the idiom “to put the boot in”, which literally means “to equip a car with a covered space at the back or front in which to carry things such as luggage and shopping”, and idiomatically means “to attack another person by saying something cruel, often when the person is already feeling weak or upset”. While the literal meaning refers to the large boot space of Mégane Classic IT, the idiomatic meaning is a sneering remark aimed at the competitors of the car manufacturing company Renault.

Conclusion

Wordplay has been shown to be an effective means of fulfilling the persuasive function of promotional language in business communication by capturing and holding the reader’s attention. One of the most intriguing aspects of wordplay is the interrelationship between language and culture, which can render the disambiguation of the intended double meanings particulary challenging and stimulating, especially if the reader is not a native speaker. This, I believe, is at least one of the reasons why commercial advertising can provide the EFL teacher with a rich source of material for analysing together with the students the stylistic features of a very popular text type in business discourse and raising awareness about the cultural background that gives rise to them.

Footnote

1 All the dictionary definitions reported in this article have been taken from Macmillan English Dictionary, 2002, © Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 2002.

References

Armao, M. (1997). Wordplay in English and Italian Written Adverts and the Implications for Translation. Unpublished MA Dissertation. Birmingham: Centre for English Language Studies (CELS), Department of English Language Studies, University of Birmingham.

Baker, M. (1992). In Other Words. A Coursebook on Translation. London and New York: Routledge.

Cook, G. (2001). The Discourse of Advertising. London and New York: Routledge.

Delabastita, D. (1996). Introduction. In D. Delabastita (ed.), Wordplay & Translation. Special Issue of The Translator, 2(2), 127-139.

Goddard, A. (2002). The Language of Advertising. London and New York: Routledge.

Haug, W.F. (1971). Kritik der Warenästhetik. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Laviosa, S. (2005). Linking Wor(l)ds. Lexis and Grammar for Translation. Napoli: Liguori.

Lund, J.V. (1947). Newspaper Advertising. New York: Prentice-Hall.

MACMILLAN ENGLISH DICTIONARY (2002). Oxford: Macmillan.

Tanaka, K. (1994). Advertising Language. London and New York: Routledge.

Taronna, A. (2005 forthcoming). Interrogating the Language of Advertising. Dis/similarities between English and Italian Ads. Bari: Papageno.

Williamson, J. (1983). Decoding Advertisements. Ideology and Meaning in Advertising (Ideas in Progress). London: Marion Boyars Publishers.

_____

© The Author 2005. Published by SDUTSJ. All rights reserved.

Scripta Manent 1(1)

» G. Crosling

Language Development in a Business Faculty in Higher Education: A

Concurrent Approach

» J. C. Gimenez

The

Language of Business E-Mail: An Opportunity to Bridge Theory and

Practice

» S. Laviosa

Wordplay

in Advertising: Form, Meaning and Function

» M. L. Pérez Cañado and A.

Almagro Esteban

Authenticity

in the teaching of ESP: An Evaluation Proposal

Business English in Practical Terms

Other Volumes